The recent refusal by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) of NAGHEDI’s application to register its woven neoprene pattern offers a useful point of comparison with one of the most frequently cited successes in fashion trademark law: Bottega Veneta’s registration of its leather intrecciato weave. Taken together, the two matters illustrate the practical limits of pattern protection under trademark law, and the difference between visual design as a brand signature and as a legally protectable trademark.

Both brands rely on weaving as a central element of their visual identity, building recognition through texture, repetition, and material consistency. The different outcomes reflect a core principle of trademark doctrine: design is protected only where consumers perceive it as indicating the source of the goods, not merely as part of a brand’s aesthetic.

Design Distinctiveness: Ornamentation and Source Identification

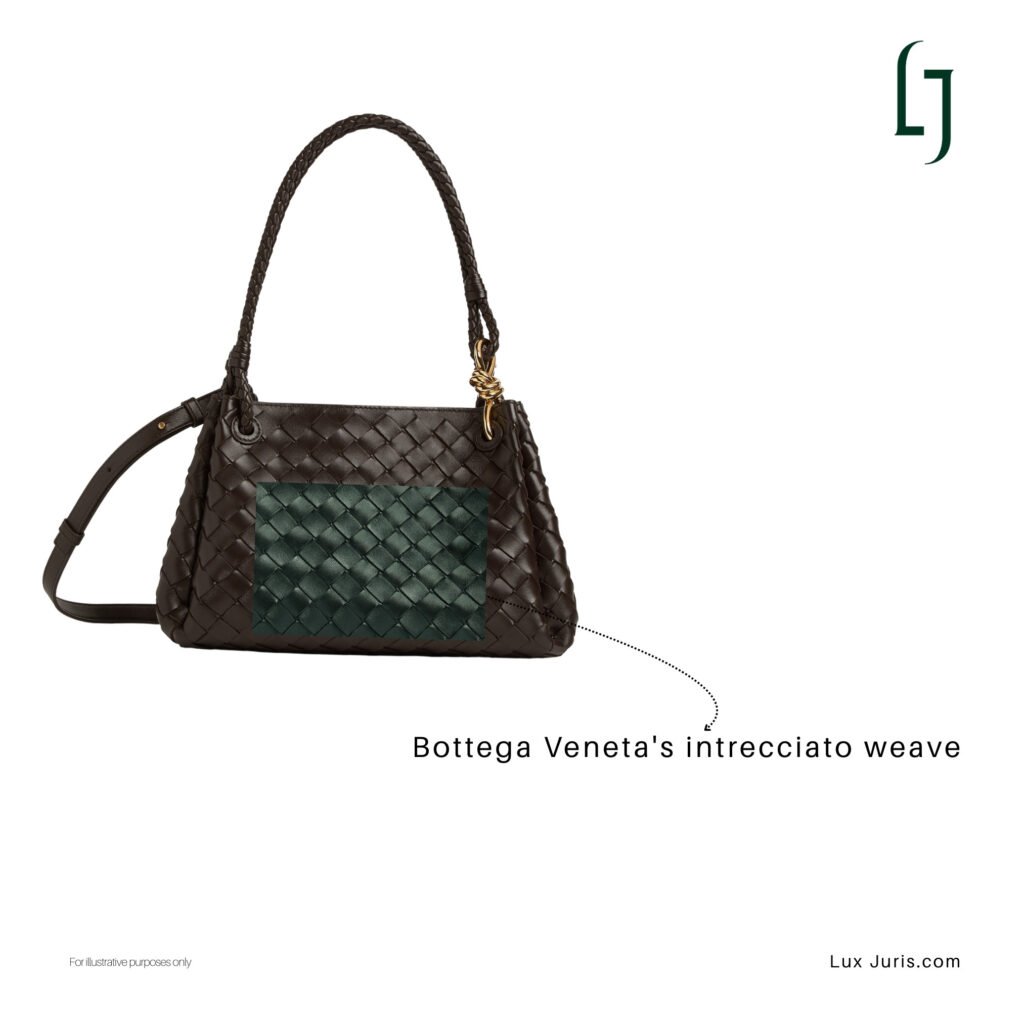

Bottega Veneta and the Intrecciato Weave

Bottega Veneta’s intrecciato consists of a precise configuration of narrow leather strips, interlaced at a defined angle and applied consistently across the brand’s leather goods. The weave is not accompanied by logos or wordmarks, and instead operates as a standalone visual identifier.

During examination, the USPTO initially treated the weave as ornamental and raised concerns of aesthetic functionality, on the basis that woven leather is a common design technique. On appeal, however, the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board accepted that, in the context of actual market use, the intrecciato had acquired the capacity to function as a source-identifying mark.

This conclusion was supported by several factors, including consistent use of the same weave across product lines, press and industry recognition of the weave as a signature Bottega feature, marketing materials positioning the weave as a core brand element, and limited use of the same configuration by competitors. Taken together, these elements supported the view that the weave had moved beyond decoration and had come to operate as trade dress capable of functioning as a trademark.

NAGHEDI and the Ornamental Threshold

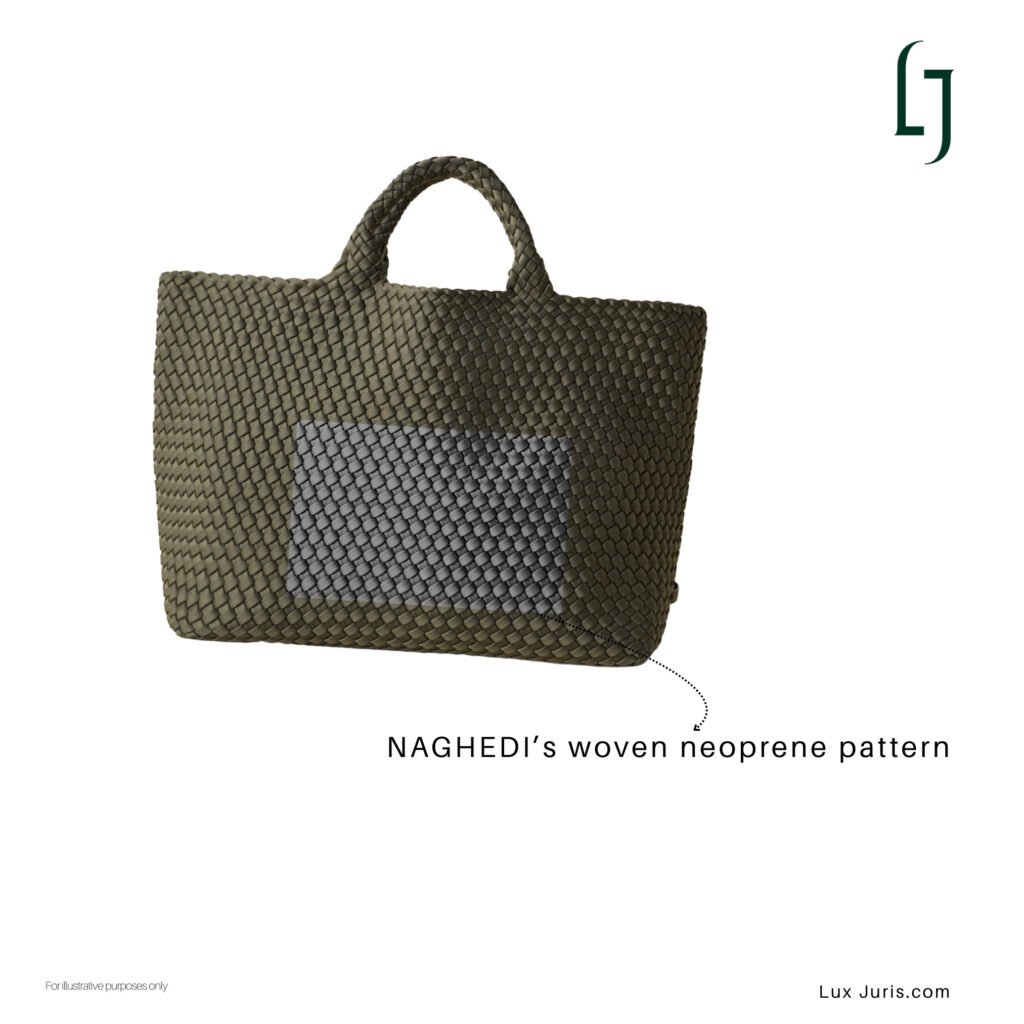

NAGHEDI’s woven neoprene pattern is formed by slim, uniform straps across its handbags. Although central to the brand’s products, it could not be shown to function as a source identifier.

The USPTO concluded that consumers were likely to perceive the pattern as a decorative surface design rather than a source identifier. This assessment was influenced by the prevalence of similar woven neoprene designs across the market, which made it difficult to treat the pattern as visually exclusive.

The Office identified several factors relevant to this assessment, including the generic nature of the weaving technique, extensive third-party use, and the absence of a sufficiently distinctive configuration linking the pattern specifically to NAGHEDI. In this context, the design was characterised as ornamental rather than distinctive for trademark purposes.

Acquired Distinctiveness and Secondary Meaning

For designs that are not inherently distinctive, trademark protection depends on proof of secondary meaning, namely evidence that consumers recognise the design as originating from a single commercial source.

Bottega Veneta

Bottega’s registration was supported by evidence demonstrating that the weave itself had become a recognised brand indicator. This included long-term use, consistent visual deployment, and sustained media treatment referring to the intrecciato as a signature Bottega element.

The Trademark Trial and Appeal Board accepted that consumers associated the weave, on its own, with Bottega Veneta, satisfying the legal requirement for acquired distinctiveness.

NAGHEDI

NAGHEDI relied primarily on sales figures, advertising efforts, and claims of competitor imitation. The USPTO found this insufficient, noting that commercial success and copying do not, by themselves, establish secondary meaning.

No consumer surveys or comparable evidence were provided to show that buyers associated the woven pattern specifically with NAGHEDI. In the absence of such evidence, the application remained vulnerable to refusal.

Scope and Precision of the Trademark Claim

Claim drafting played a significant role in shaping the examination outcomes.

Bottega’s registration was based on a narrowly defined description of the weave, specifying the orientation and method of interlacing. This allowed the USPTO to assess the mark as a specific configuration rather than a general design concept.

NAGHEDI’s application, by contrast, claimed a broad repeating woven pattern without clearly identifying distinctive structural features. This made it more difficult to distinguish the claimed design from common woven styles in the market.

As a general matter, broad claims over widely used design elements are more likely to encounter objections based on ornamentation and lack of distinctiveness.

Market Context and Exclusivity

Trademark distinctiveness is assessed in context, and the level of competition within a given product category is directly relevant.

Bottega’s intrecciato operated in a relatively uncluttered visual environment, with limited use of similar configurations by other brands. This supported the argument that the weave functioned as a proprietary brand signal.

NAGHEDI’s design operates in a more crowded segment where woven neoprene patterns are widely used across brands and price points. This market context made it harder to establish that the pattern was perceived as a unique source identifier.

In saturated design markets, patterns are generally treated as decorative unless supported by strong and consistent evidence of distinctiveness.

Trademark law does not protect design for its own sake. It protects design only to the extent that it operates as a sign of origin.

Conclusion

The comparative analysis of Bottega Veneta and NAGHEDI ultimately reveals something more fundamental than divergent registration outcomes. It shows how trademark law is primarily concerned with meaning and consumer perception.

Bottega’s registration reflects the ability of a design feature to acquire trademark meaning through consistent use, market recognition, and evidentiary support. NAGHEDI’s refusal reflects the difficulty of establishing distinctiveness for patterns that operate within a crowded and stylistically conventional design space.

Distinctiveness in fashion trademark law turns on consumer perception. Visual recognisability is necessary, but not sufficient, as the pattern must be recognised as a mark in law, with sufficient distinctiveness to indicate source.