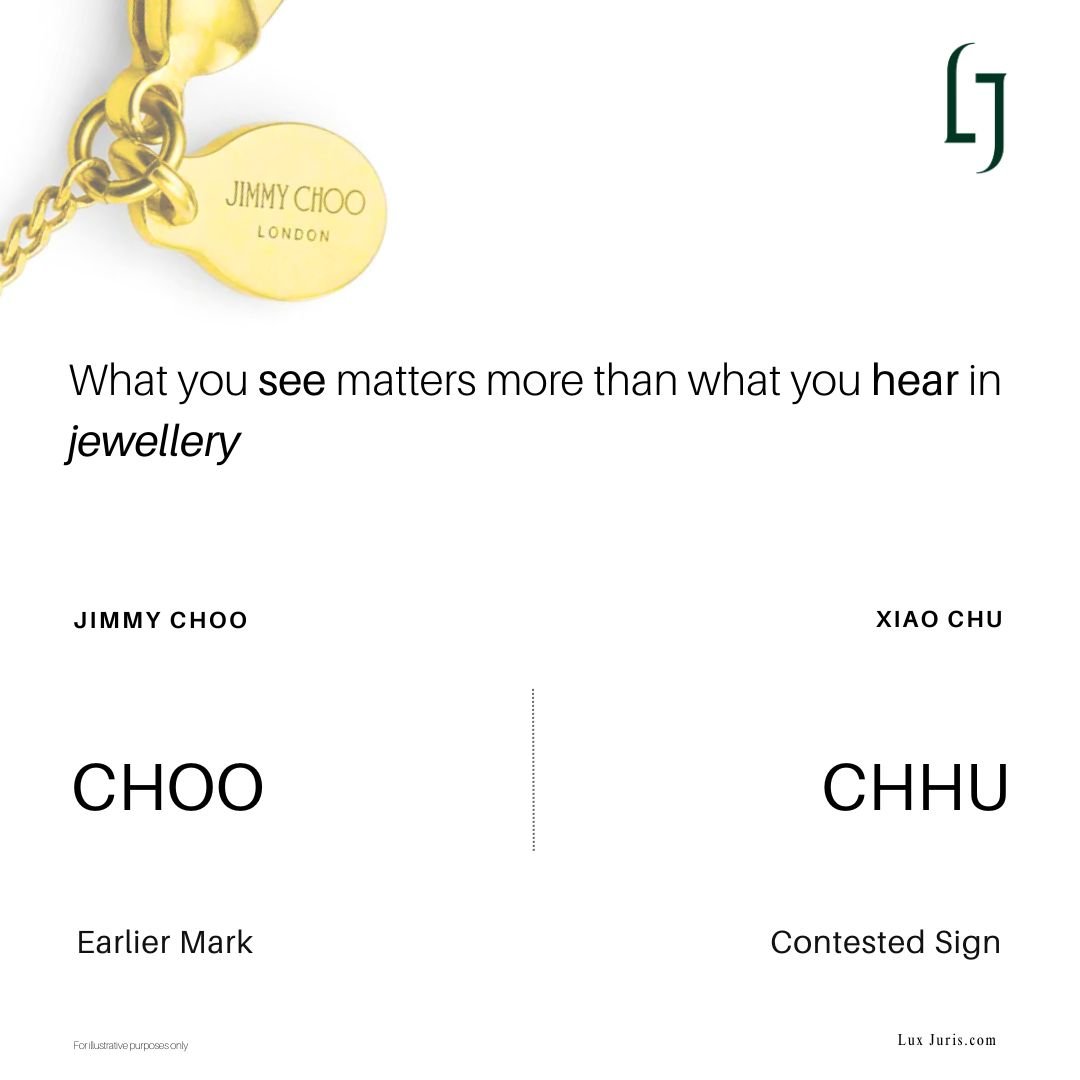

On 4 September 2025, the EUIPO Opposition Division delivered a decision that quietly reaffirmed a fundamental principle in trade mark protection for the luxury and design industries, the eye matters more than the ear. In this opposition, British luxury house J. Choo Limited, owner of the JIMMY CHOO brand, sought to block registration of CHHU, a word mark filed by Xiao Chu of Antwerp for jewellery. The outcome turned on the boundaries between visual distinctiveness, phonetic overlap, and the heightened discernment of luxury consumers.

The context of the opposition

The dispute arose when Xiao Chu applied to register the European Union trade mark CHHU in Class 14, covering a range of jewellery goods such as bracelets, necklaces, brooches and diamond jewellery. In October 2024, Jimmy Choo opposed the application on the basis of several earlier registrations, including the word marks CHOO and JIMMY CHOO, and their figurative variants, all protected across the European Union and under international designations.

The opposition was initially based on two distinct legal grounds under the European Union Trade Mark Regulation (EUTMR):

Article 8(1)(b) EUTMR, which protects earlier marks against a likelihood of confusion; and

Article 8(5) EUTMR, which protects reputed marks against unfair advantage.

By February 2025, Jimmy Choo withdrew its reliance on Article 8(5) and limited the opposition to Article 8(1)(b), focusing only on two earlier marks: the word mark CHOO and one corresponding figurative registration. The case thus turned on whether the short, four letter CHHU could be mistaken for CHOO when used for identical goods.

Identical goods, but a high level of consumer attention

The EUIPO confirmed that the goods covered by both marks were identical, since terms such as jewellery and ornaments appeared in both lists. The relevant public was defined as the general public and professional consumers with specific knowledge or experience in the jewellery sector.

The Opposition Division recalled that jewellery purchases involve a relatively high degree of attention. These goods are often luxury items or intended as gifts. Buyers typically examine them carefully before purchase. This assumption of a discerning consumer would later prove decisive in the overall assessment.

Comparison of the signs

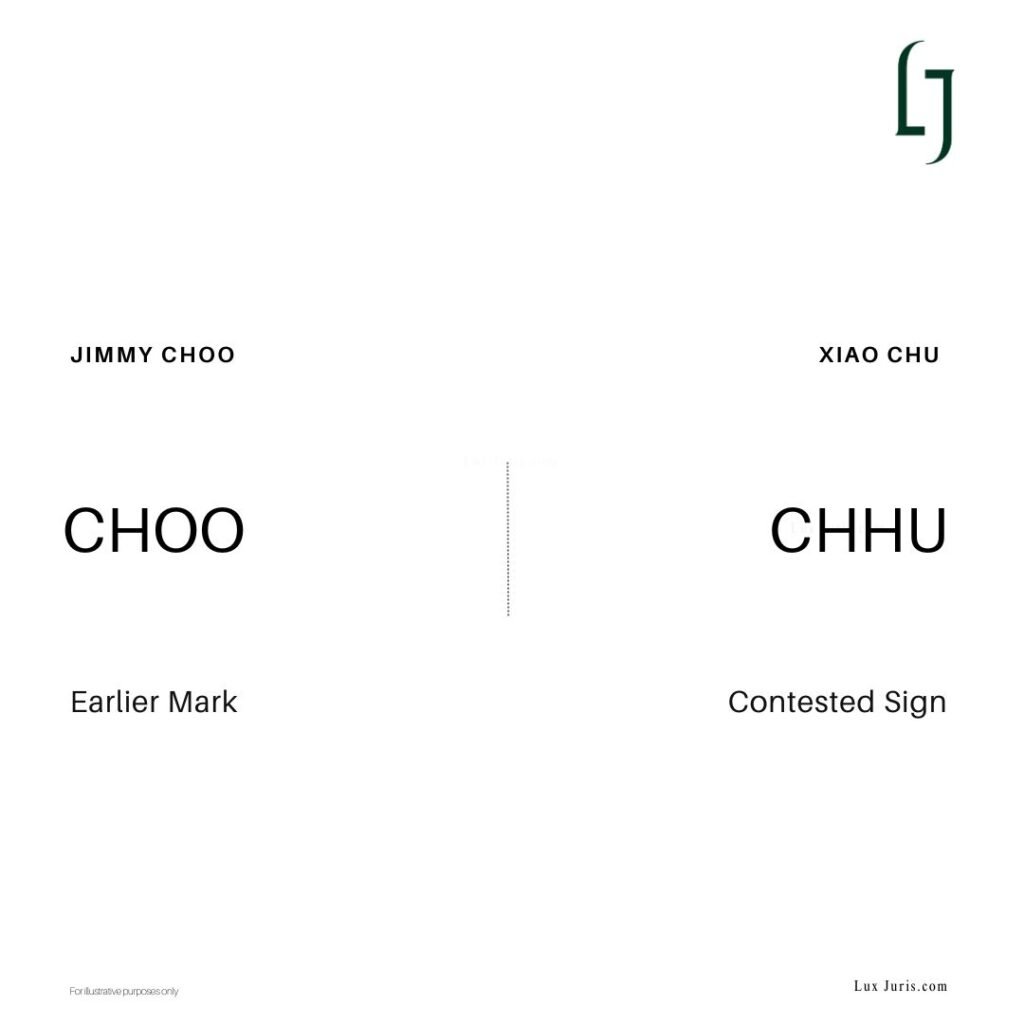

At the heart of the dispute were the two signs:

Both were short word marks of four letters, beginning with “CH” and lacking any meaning. As both were invented words, there was no conceptual similarity to assess. The analysis therefore focused on their visual and phonetic characteristics.

Visual comparison

Visually, the marks shared their initial two letters but diverged sharply in their endings. “CHOO” concluded with double vowels, whereas “CHHU” ended with a double consonant cluster. The EUIPO noted that when marks are short, minor visual differences become significant. The unusual “CHH” sequence, containing three consecutive consonants, would be easily noticed by English speaking consumers.

The Office therefore found the marks visually similar to a below average degree.

Phonetic comparison

Phonetically, however, both signs could resemble the pronunciation of the English word “chew”. The Office accepted that consumers might drop the second “H” when pronouncing “CHHU”, resulting in aural identity between the two.

Still, this identity in sound was not sufficient to establish confusion.

The global assessment

In its global assessment, the EUIPO weighed all relevant factors: the similarity of goods, the distinctiveness of the earlier mark, and the manner in which the goods are marketed. The goods were identical, and the earlier mark had a normal degree of distinctiveness. Yet jewellery and luxury accessories are typically chosen visually, not orally. Consumers see and evaluate them in boutiques, catalogues or online platforms rather than ordering them by name in noisy environments.

This purchasing context places greater weight on visual differences. The EUIPO therefore held that the visual perception of the marks was decisive. Even though the marks were aurally identical, the pronounced visual difference between “OO” and “HU” would not escape notice. For luxury buyers who exhibit heightened attention, the visual contrast was more than sufficient to prevent confusion.

Outcome of the decision

The EUIPO concluded that there was no likelihood of confusion within the meaning of Article 8(1)(b) EUTMR. The phonetic identity of the marks was outweighed by their visual differences and by the attentiveness of consumers. The opposition was rejected in full.

Jimmy Choo’s additional reliance on a figurative mark did not alter the result, as its stylised elements created even less similarity to the contested mark. The opponent was ordered to bear the costs of the proceedings.

For designers and luxury brands

This decision offers several instructive lessons for fashion and jewellery designers seeking to protect or develop distinctive marks:

Phonetic similarity is not decisive

Even identical pronunciation will not establish confusion if consumers primarily perceive the goods visually. For luxury goods, visual distinction takes precedence.

Short marks magnify small differences

When a mark consists of only a few letters, minor variations in structure or rhythm can prevent confusion. The unusual consonant sequence in “CHHU” proved crucial.

Luxury goods imply heightened consumer attention

Buyers of high-end jewellery or accessories observe details carefully, reducing the likelihood that similar-sounding marks will be confused.

Market context shapes the assessment

The Office emphasised how goods are sold and encountered. In visually driven sectors such as jewellery or fashion, aural similarities carry less legal weight.

Strategic use of Article 8(5)

Jimmy Choo initially invoked the protection for reputed marks but withdrew it. While reputation can extend protection beyond confusion, it demands strong evidence. Its absence confined the case strictly to visual and phonetic analysis.

Conclusion

The decision illustrates how the EUIPO approaches short word marks. Visual differences were given greater weight than phonetic similarities. When consumers encounter products directly, what they see carries more influence than what they hear.

In the jewellery sector, where purchases are deliberate and visually guided, phonetic similarity alone was insufficient to create confusion. CHHU and CHOO may sound alike, yet their visual distinction was clear enough to avoid any mistaken association.

The ruling also establishes that even when goods are identical, confusion does not arise if the marks can be clearly differentiated by sight.

In the language of luxury, and in the eyes of the EUIPO, confusion begins with what is seen, not with what is heard.

Source: