Minimalism, Geometry and the Limits of Trade Mark Protection.

The EUIPO decision of 12 December 2025 refusing registration of Charlotte Tilbury’s figurative mark confirms, in clear terms, the continued strict application of Article 7(1)(b) EUTMR to minimalist signs. The Office found that the mark, assessed on its own, is devoid of inherent distinctive character for the Class 3 goods claimed.

The decision does not turn on the reputation of the brand or on any assessment of its strategy. The sole question was whether the sign itself enables the average consumer to identify the commercial origin of the goods. The EUIPO concluded that it does not.

The sign and the objection

The application covered a broad range of Class 3 goods, including cosmetics, skincare products, perfumes, toiletries, and cleaning and polishing preparations. The relevant public was therefore the general consumer of everyday cosmetic and personal care products.

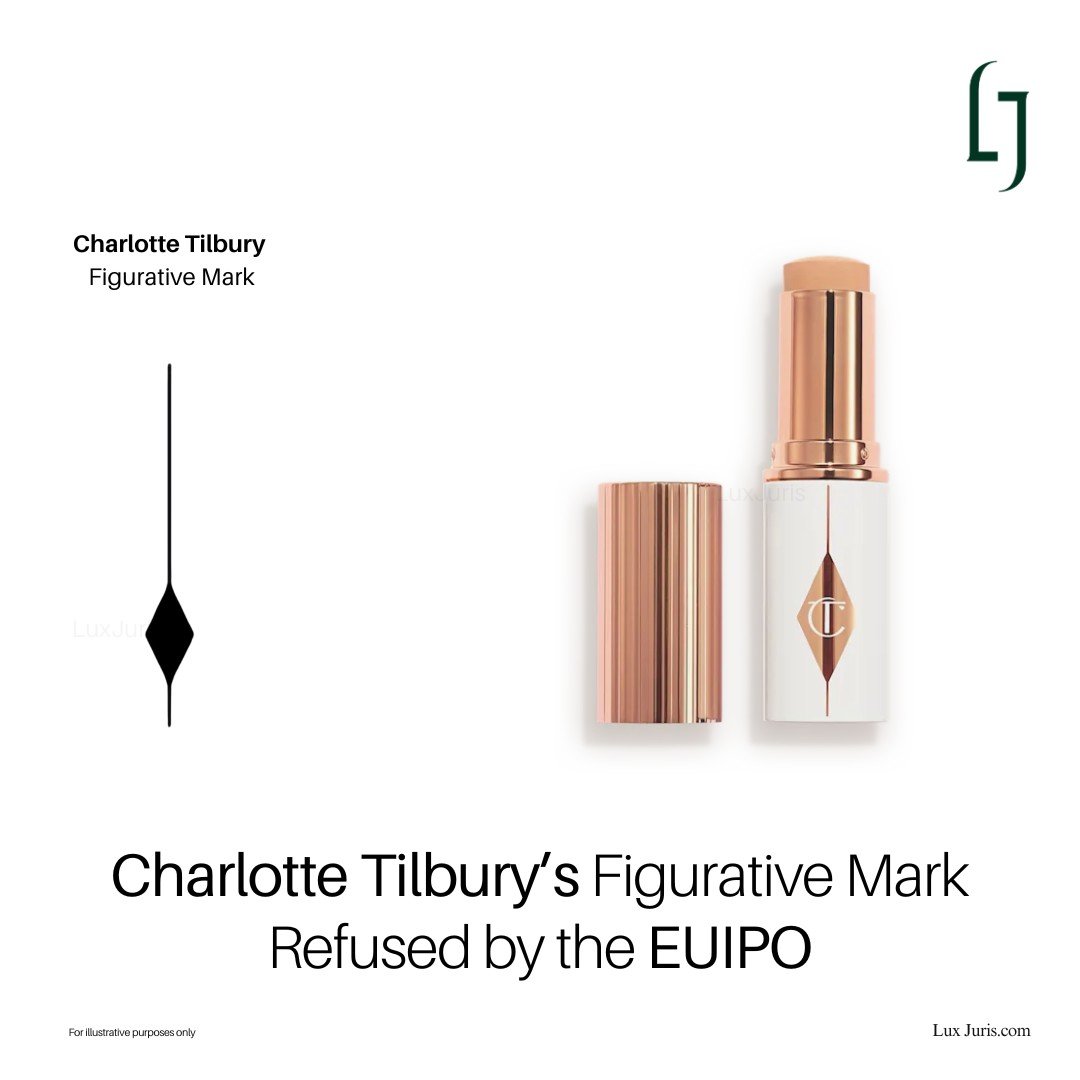

The mark applied for is a figurative sign consisting of a simple geometric configuration. The Office described it consistently as an elongated black square placed on a line. In the EUIPO’s assessment, the sign would be perceived as a simple figurative element, incapable of transmitting a trade mark message.

There was no verbal element and no additional figurative feature capable of conferring even a minimum degree of distinctiveness. On that basis, the Office raised an objection under Article 7(1)(b) EUTMR.

The applicant’s arguments

The applicant disputed the Office’s characterisation of the sign. It argued that the mark should be understood as a diamond or rhombus intersected by a line, producing contrast between thickness and thinness and creating visual tension. According to the applicant, this configuration was unusual, aesthetically balanced and capable of being remembered by consumers.

It was further argued that consumers are accustomed to simple and stylised figurative marks and that the sign reflects contemporary branding trends, including what the applicant described as “quiet luxury”. Several earlier Board of Appeal decisions involving geometric marks were cited in support. The applicant also referred to registrations of the same sign in the United Kingdom and in Bahrain, Oman, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

In the alternative, a subsidiary claim of acquired distinctiveness through use was raised.

Why the EUIPO maintained the refusal

The EUIPO rejected the applicant’s submissions and maintained the refusal.

First, it reiterated settled case law and Office practice according to which extremely simple signs composed of basic geometric figures are incapable, as such, of conveying a message that consumers can remember, unless they depart significantly from the norms or customs of the relevant sector. This applies equally where such figures are combined, if the overall impression remains simple and commonplace.

Secondly, the Office rejected the applicant’s attempt to reframe the sign. Even assessed as a whole, the mark was found to consist merely of an elongated square and a line, with no unusual characteristics. The EUIPO considered that the relevant consumer would perceive the sign as banal ornamentation rather than as an indication of commercial origin.

The Office expressly stated that the sign was not striking, not easily memorable and incapable of distinguishing the goods of one undertaking from those of others. The absence of any additional element capable of showing distinctiveness was decisive.

The quiet luxury argument

The EUIPO addressed, and dismissed, the applicant’s reliance on “quiet luxury”. It noted that this concept relates to product quality, craftsmanship and restrained branding, rather than to the inherent distinctiveness of a trade mark sign.

Even where understatement is intentional, the sign must still meet the minimum legal threshold required to function as a trade mark. In the Office’s view, this threshold was not met.

Precedent and foreign registrations

The EUIPO rejected reliance on earlier Board of Appeal decisions, reaffirming that trade mark registration decisions are adopted within circumscribed powers and are not discretionary. Registrability must be assessed solely on the basis of the EUTMR as interpreted by the EU courts, not by reference to previous Office practice.

The cited decisions were found not to be comparable, either because the signs differed materially, the goods were different, or examination practice and market conditions had evolved since those decisions were issued.

Registrations obtained outside the European Union were also held to be irrelevant. The EU trade mark system is autonomous, and the Office is not bound by national or third-country decisions.

What happens next

The refusal concerns only inherent distinctiveness under Article 7(1)(b) EUTMR. The EUIPO expressly stated that the examination of the subsidiary claim based on acquired distinctiveness under Article 7(3) EUTMR will follow once the present decision becomes final.

Any success at that stage will depend on concrete and substantiated evidence showing that the relevant public already associates this specific geometric sign with a single commercial origin.

Conclusion

This decision does not reject minimalist branding as such. It confirms, however, that basic geometry remains difficult to protect under EU trade mark law unless it clearly departs from what consumers already perceive as decoration.

In markets such as cosmetics, where simple forms are common, restraint alone is not enough. However refined the design may be, trade mark protection still requires a sign that consumers can immediately recognise as a badge of origin.