Fashion that is no longer in trend, whether hanging in your closet or donated to charity, does not simply disappear. Many garments find their way to bustling markets far from where they began. Senegal, in West Africa, is one of the countries where this secondhand fashion trade thrives.

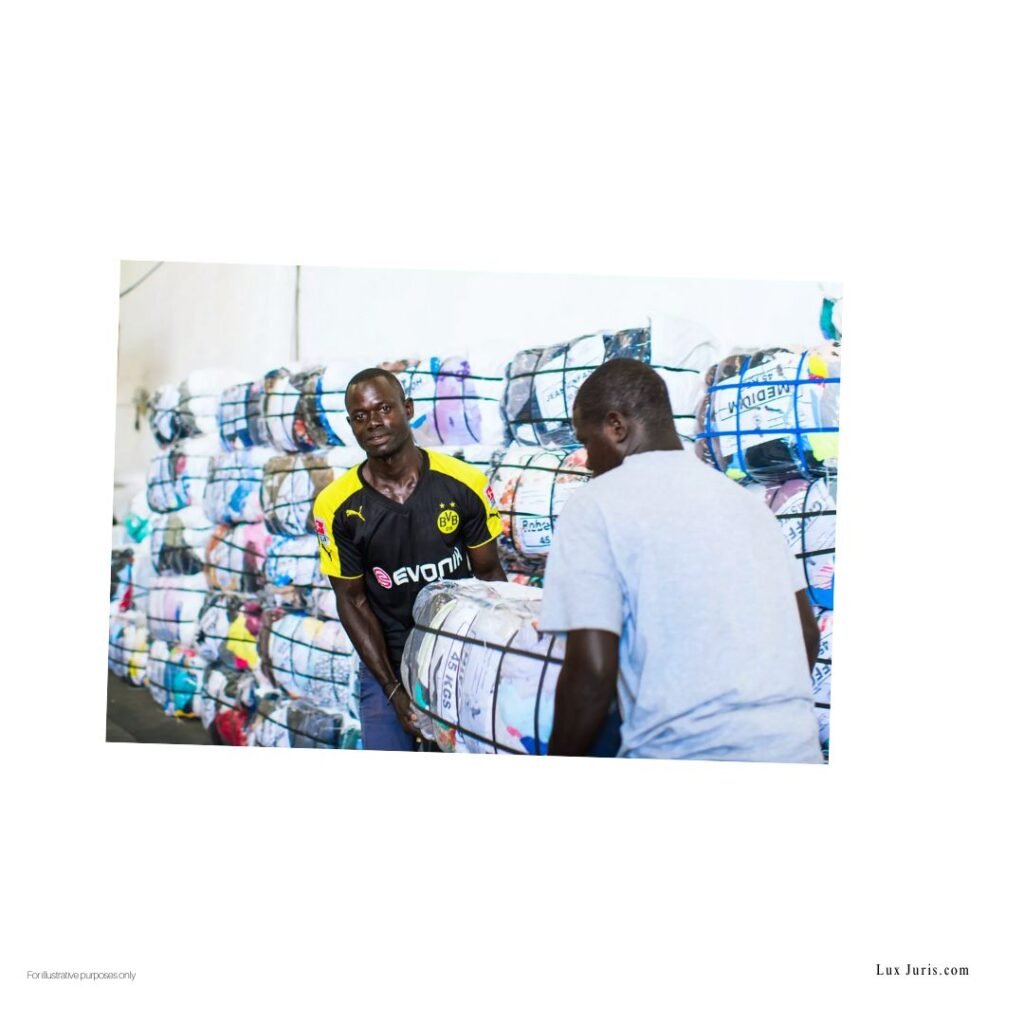

In Senegal, feugue-diaye (“clean off and sell”) is a thriving secondhand clothing culture, reminiscent of American thrifting but with its own rhythm. Clothes arrive from Europe, the US, and beyond in 45-kilogram bales, sorted by hand, graded for quality, and sold in open-air markets. Each piece is given a new life, restyled, repurposed, redefined.

“It’s now mandatory to go to the markets before I go shopping at any actual department store because, I swear, you’ll find everything you need plus stuff that you don’t need but still come home with you.”

– Ndeye Awa Wone, Senegalese immigrant

Feugue-diaye is more than a shopping trip. It is a living archive of global fashion and a visible form of circular fashion in motion. Every garment tells a story of overproduction, shipping, and reuse. It also prompts a question: is thrifting replacing buying new, and what does that mean for fashion’s future?

Import Flow into Senegal’s Secondhand Fashion Markets

Most secondhand clothing in Senegal arrives packed into large bales from the UK, US, and other Western countries. In Dakar, wholesalers like Frip Éthique, a social enterprise run by Oxfam, sort them into “tropical mixes” for resale to neighbourhood vendors.

Oxfam, which opened the UK’s first charity shop in 1948, now runs over 600. Clothing is collected through shop donations, textile banks, retailer partnerships such as M&S’s scheme, and workplace drop off points. All is sent to Oxfam’s Wastesaver facility in West Yorkshire, where items are sorted for resale, reuse, or recycling. Roughly 30% (about 2,000 tonnes annually) is exported to Frip Éthique

Wastesaver: Sorting, Repurposing, and Minimising Waste

At Oxfam’s Wastesaver warehouse, donated clothing is sorted along large conveyor belts by trained staff, who carefully separate items based on their condition and potential for reuse. The primary aim is to maximise reuse and minimise waste. Almost everything that comes through the facility is diverted from landfill in some way.

Damaged or unsellable textiles are usually repurposed. Some become wiping cloths or industrial rags, others are recycled into insulation, mattress stuffing, or other materials. Only a very small percentage of donations, typically heavily soiled or non recyclable fabrics end up being classified as residual waste and are sent to landfill or incineration as a last resort.

Any leftover or lower-quality garments that are still wearable may be legally exported to international resale markets like Frip Éthique (Oxfam).

Import Restrictions in Africa

These clothes cannot go just anywhere. Many African countries have rules regulating what secondhand clothing can be sold and what is prohibited.

Not all countries accept secondhand imports;

Senegal: No ban or quality controls, relying on market demand.

Rwanda: Outright ban.

Nigeria: Enforces quality checkpoints.

South Africa: allows only for charitable use.

While environmental concerns drive some bans, many African economies depend on secondhand imports for affordable clothing and income.

Tracking the Life of Garments Beyond First and Second Use

It would be ideal to have regulations that track the life of garments beyond their second use, and legal frameworks are beginning to move in that direction.

The European Union’s Strategy for Sustainable and Circular Textiles (2022) proposes a Digital Product Passport, a legal tool designed to track materials, production, and usage history across a garment’s full lifecycle beyond initial use and resale.

This strategy builds upon the EU Waste Framework Directive (2008/98/EC), which supports the principle of Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR), holding producers legally accountable for the management of their products.

Furthermore, under the Basel Convention, which regulates the international movement of waste, efforts are underway to classify textile waste more strictly and to improve traceability of exported garments, particularly to the Global South.

These instruments reflect a growing legal consensus that monitoring garments throughout their lifecycle is critical to reducing environmental harm, improving accountability, and supporting circular economy goals.

Given the volume of textile waste globally, should other countries follow Europe’s lead by adopting similar legal instruments?

Liability

Accountability is complex and can fall under multiple actors depending on jurisdiction and circumstances.

Many jurisdictions adopt or are developing Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) programmes, which legally require brands and manufacturers to take responsibility for the entire lifecycle of their products, including post-consumer waste (UK Environment Act 2021).

However, importers, exporters, and even consumers can be held liable for environmental harm depending on their actions with the clothing. Responsible parties may face fines or remediation orders (US Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, RCRA).

So ask yourself prior to disposal: If I throw this top away, will it just end up in a landfill in Africa, or could I be held legally responsible for environmental harm?

Conclusion

Senegal’s feugue-diaye markets reveal a dual truth about the global fashion cycle. They are proof that clothing can have a second, even third life, yet they also lay bare a global trade system that too often shifts the environmental and economic burden onto countries least responsible for overproduction.

Accountability must move beyond slogans about sustainability. Brands, retailers, and exporters should be required to maintain visibility over the afterlife of their garments, including what happens when they cross borders. This means designing for durability, using traceable supply chains, and ensuring that exports are genuinely reusable rather than disguised waste.

Without such measures, secondhand fashion markets will continue to absorb the consequences of unchecked production, often without adequate regulation or infrastructure to manage the volume. True circularity is not simply about extending the life of clothing, but about ensuring that its movement across the world does not create new forms of harm. The responsibility for this shift lies not with the markets of Dakar, but with the producers, distributors, and consumers who set the cycle in motion.

Author: Assy Sy | Research: Assy Sy | Editor: Qazi

Sources:

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/

https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/31079d7e-3a96-11eb-b27b-01aa75ed71a1/language-en

https://environment.ec.europa.eu/strategy/circular-economy-action-plan_en

https://www.zagumi.com/exporting-second-hand-clothing-to-africa/ https://www.zagumi.com/exporting-second-hand-clothing-to-africa/ https://committees.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/97372/html

Image:

- Oxfam’s Frip Éthique warehouse in Dakar, Senegal, sorting secondhand clothing bales. (Image: Rachel Manns Photography/Oxfam, source: mirror.co.uk)