POLO, Ralph Lauren’s long established single-word trademark used prominently across the European Union, defined the outcome of the proceedings against the application “Wellington Polo Club”. The case demonstrated how such a mark can neutralise a later registration that incorporates it in full. The Opposition Division upheld the opposition in its entirety, rejecting the application for all goods and services once the reputation of the earlier mark, the structure of the contested sign, and the applicant’s own use were examined in the course of the assessment.

The Application and the Opposition

The application for the word mark “Wellington Polo Club” was filed on 20 September 2024. It covered perfumes, cosmetics, a wide range of luggage and bags, clothing, footwear, headgear, and an extensive list of retail, wholesale, and advertising-related services.

On 30 January 2025, The Polo/Lauren Company L.P. filed an opposition based on two earlier word marks, both consisting solely of the sign POLO: one EU trade mark and one French national registration. For the EU mark, the opponent relied on reputation and for the French mark, it relied on identical or overlapping service coverage.

The Evidence of Reputation

The first task for the EUIPO was to determine whether the earlier EU mark “POLO” enjoyed a reputation before the application date. The opponent submitted extensive evidence, which included brand rankings across 2000-2023 showing Ralph Lauren among the most valuable global brands, with specified valuations for 2015 and 2016, together with advertising campaigns used in various Member States. These materials covered Paris storefronts, seasonal campaigns, sneaker promotions, and broad marketing materials where “POLO” appears prominently.

The evidence also comprised press articles in English and French publications discussing the history and standing of the POLO brand, as well as evidence of use of “POLO” together with product lines such as POLO GOLF, POLO TENNIS, and POLO SPORT. Further documentation was provided on the brand’s visibility through its long association with major sporting events such as Wimbledon and the US Open, placing the POLO mark within a wide public setting that supports its recognition.

The opponent additionally submitted numerous product catalogues from 2019 to 2022 showing “POLO” used independently and consistently, along with substantial EU-level and France-specific sales figures confirmed by corporate officers. The Office noted that although the material also displayed “RALPH LAUREN” and the polo player logo, the word “POLO” appears independently in large lettering and remains clearly identifiable as a separate mark.

On that basis, the EUIPO concluded that the earlier EU trade mark “POLO” enjoys a strong reputation in the European Union, at least for clothing in Class 25.

Comparison of the Signs

The earlier mark consists solely of the word “POLO”. The contested sign contains that word in full as its central element, placed between “Wellington” and “Club”.

The Office found the signs visually and aurally similar to at least a low degree because of the full incorporation of the earlier mark. Conceptually, both refer to polo as a sport, with the contested sign adding the idea of a polo club associated with a place or name such as Wellington. The Office confirmed that even for consumers who associate “polo” with certain clothing styles in some languages, the earlier word retains at least a minimum inherent distinctiveness.

Establishing the Link

Having found similarity and reputation, the EUIPO examined whether the public would make a connection between the signs when encountering the contested mark on the relevant goods and services.

The Office held that consumers would indeed establish such a link. It reasoned that established clothing brands commonly expand into perfumery, cosmetics, bags, luggage, umbrellas, and similar lifestyle goods. The contested goods in Classes 3, 18, and 25 fit naturally within this pattern. The retail and wholesale services directed at clothing, footwear, headgear, bags, and perfumery also fell within a commercial environment where consumers expect brand coherence and brand extensions.

The earlier mark’s reputation, combined with the identical appearance of “POLO” at the centre of the contested sign, made it likely that the public would associate the later sign with the earlier reputed mark.

Unfair Advantage

With that link established, the EUIPO assessed whether the contested mark would take unfair advantage of the earlier mark’s reputation. The Office found that it would.

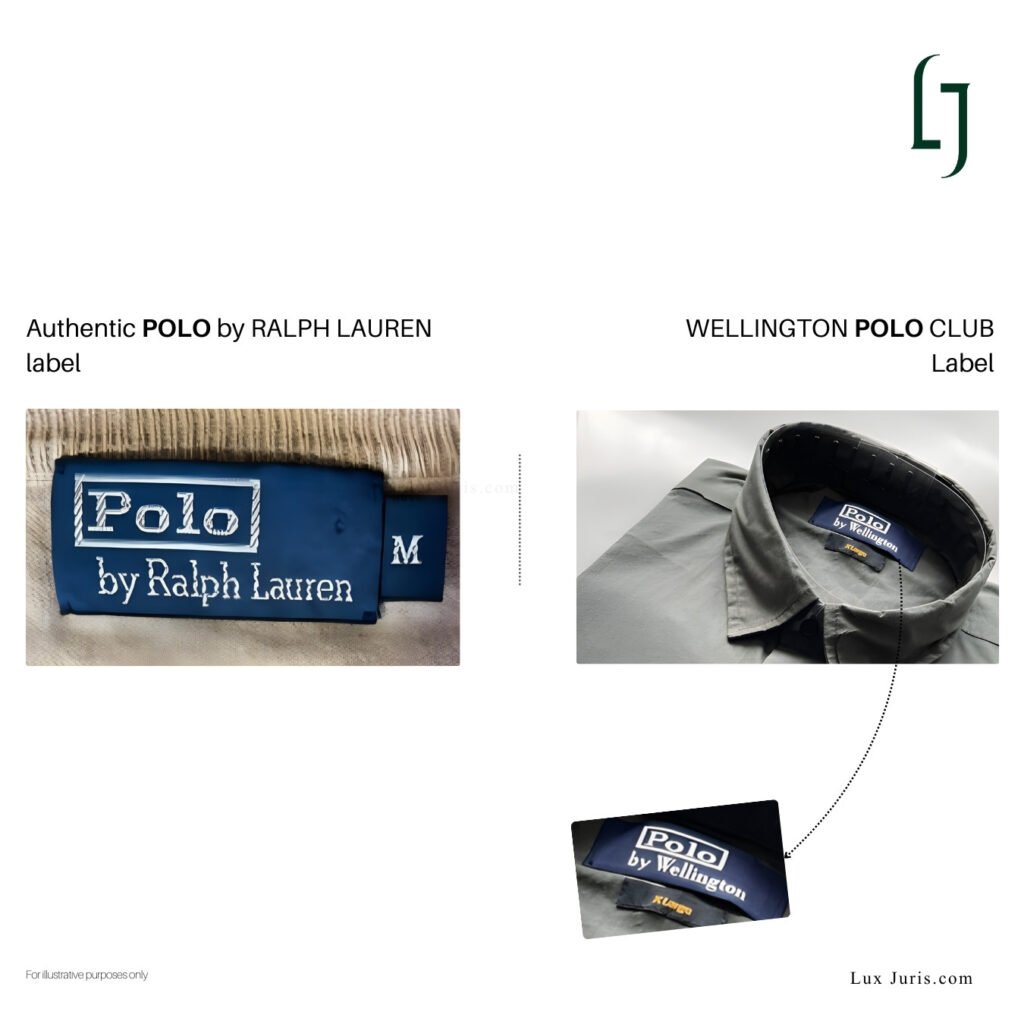

A substantial part of this conclusion derived from the opponent’s evidence of how the applicant was using the contested sign in commerce. The material showed “POLO” being used prominently, often more prominently than “Wellington”, and displayed in a manner that placed the focus on “POLO” rather than on the other elements. The applicant consistently used “1967”, which is the founding year of the POLO brand, on its products, adding an impression of historical association with Ralph Lauren.

The EUIPO paid particular attention to the presentation of perfumery products, describing the imitation as especially striking, and noting the resemblance and the déjà-vu effect created by the labels and packaging choices.

The Office concluded that the applicant’s use would allow it to benefit from the reputation, attractiveness, and commercial power generated by the earlier mark, thus taking unfair advantage of it without due cause.

This led to the refusal of all goods in Classes 3, 18, and 25, and all services in Class 35 relating to the sale of those goods.

Remaining Services and Likelihood of Confusion

The services in Class 35 that did not involve the sale of goods, such as advertising distribution, preparation of merchandising materials, business management of retail outlets, and market research, were examined separately.

Here, the EUIPO relied on the French earlier mark “POLO”, which covers advertising and business. The contested services either overlapped with or were identical to this broad category.

Even though these services target a professional public with a higher degree of attention, the Office found that the inclusion of the earlier mark in its entirety within the contested sign created a likelihood of confusion, particularly given the identity of the services. The contested sign could easily be perceived as a variant or sub-line of the earlier mark for business and advertising services. These services were therefore rejected as well.

Decision and Outcome

The EUIPO rejected the “Wellington Polo Club” application in full on5 December 2025. The decision rested on examination of the reputation of the earlier EU mark, the incorporation of “POLO” into the contested sign, the commercial proximity of the goods and services, and the reinforcement of association created by the applicant’s own use, including packaging choices and references to “1967”. Once these elements were placed together, the outcome became unavoidable: the opposition succeeded for all goods and services, and the applicant was ordered to bear the costs.

The party affected by this decision has a right to appeal.

Conclusion

The EUIPO’s decision inWellington Polo Club shows how a single-word mark with a strong reputation, widely recognised across Europe and used on its own, can receive broad protection. The Office moved through a clear sequence: verifying reputation, assessing whether the public would establish a link, determining the presence of unfair advantage, and finally considering likelihood of confusion for the remaining services, which together led to the rejection of the application in its entirety.

For founders building fashion brands, using a name that contains the core of a long-established mark leaves very little room to operate. Fashion brands often expand into related products, and consumers expect those extensions, so even small similarities in wording or presentation can matter. If a new mark sits too close to a well-known one, it will likely be seen as taking from the older brand’s reputation.

The Wellington Polo Club case shows that this closeness on its own, even without intent, can be enough for a finding of unfair advantage when the way the mark is used makes consumers think there is a connection with the earlier POLO brand.