In fashion, a strong design is a valuable asset. But beyond aesthetics, the real test lies in whether that design can hold up in court. Pattern trademarks are intended to protect specific design configurations that help a brand stand out, but securing protection is often a complex and uncertain process. While Bottega Veneta succeeded in gaining trademark rights for its “intrecciato” weave in 2013, other brands, such as NAGHEDI, have found the path far less straightforward.

What Are Pattern Trademarks?

Pattern trademarks are a form of trade mark protection granted to specific patterns or motifs that appear on products. They are part of the visual identity of a brand and are capable of functioning as a source identifier, provided they meet the distinctiveness requirement. Unlike logos, which are immediately recognisable, patterns typically require repeated use and consistent exposure before consumers begin to associate them with a single commercial origin. To qualify for registration, a pattern must be capable of distinguishing the goods of one undertaking from those of another.

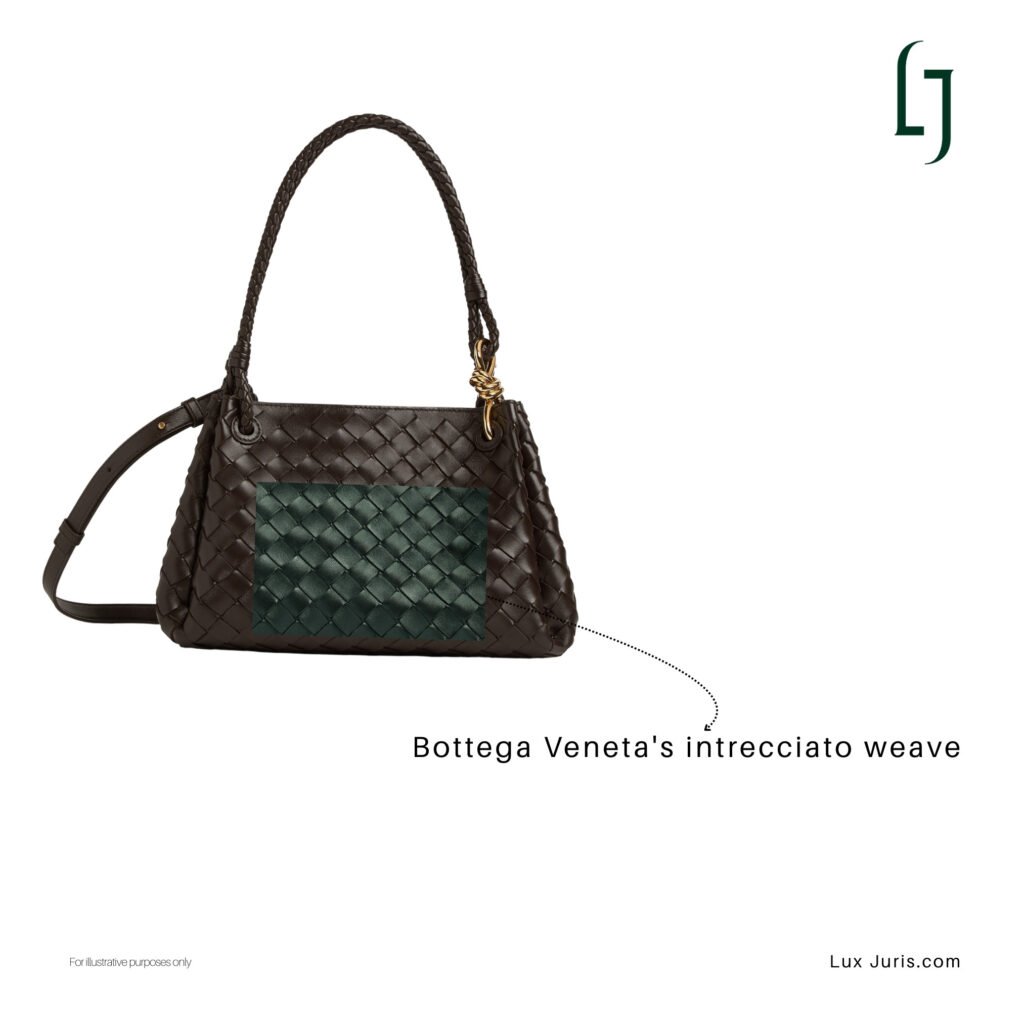

Bottega Veneta: The “Intrecciato” Weave Case

Bottega Veneta’s success with its “intrecciato” weave illustrates the importance of persistence and clarity in the trade mark process. Initially, the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) rejected the brand’s application, on the basis that the design was ornamental and functional rather than distinctive. In essence, the USPTO argued that the weave contributed more to the product’s appearance and structure than it did to its branding function.

In response, Bottega Veneta amended its application to describe the weave more precisely, referring to it as a configuration of slim, uniformly sized leather strips arranged at a 45-degree angle. The brand also submitted extensive evidence, including proof of over $22.9 million in advertising spend, to establish that the weave had acquired distinctiveness in the minds of consumers. Once this material was reviewed, the USPTO accepted that the weave had become a recognisable badge of origin and granted trade mark protection.

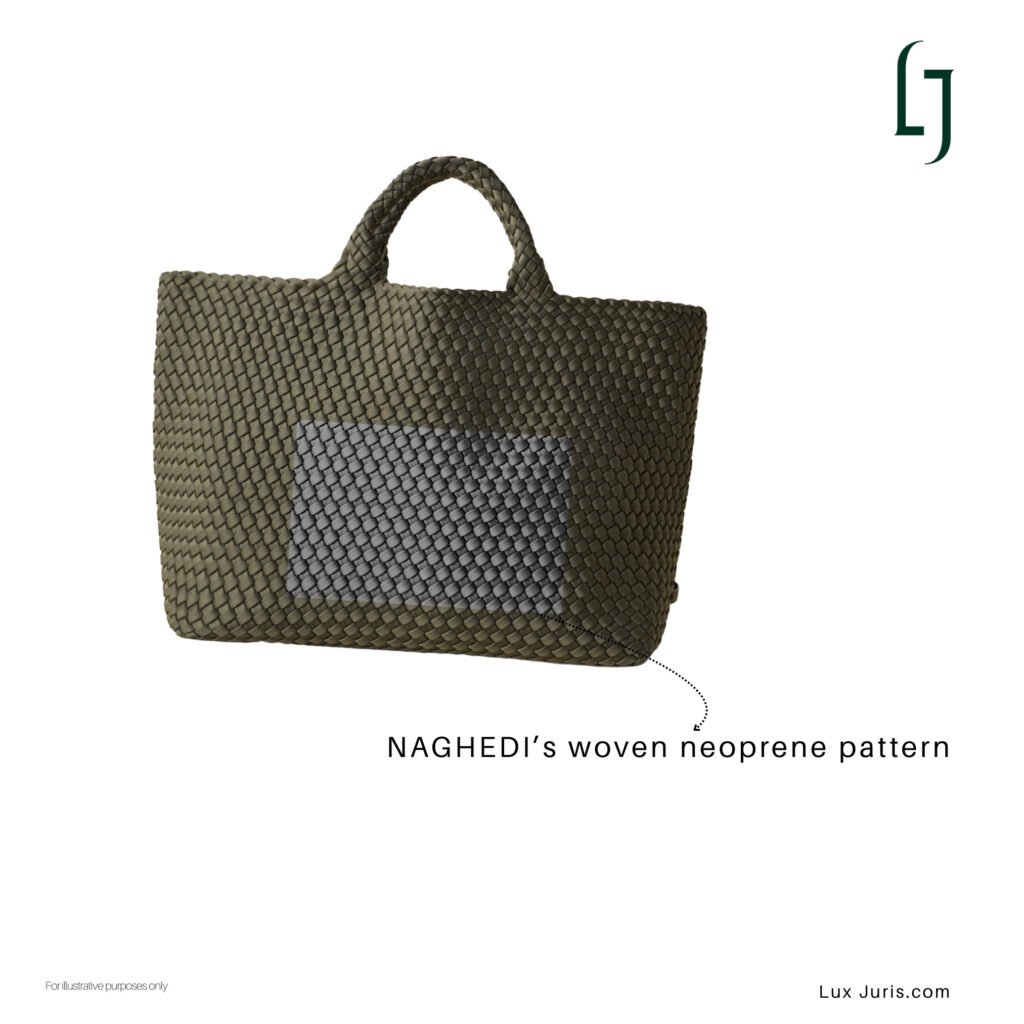

NAGHEDI: The Woven Neoprene Case

In contrast, NAGHEDI, a smaller brand known for its woven neoprene bags, has encountered difficulties in achieving similar protection. The USPTO has taken the view that the pattern lacks sufficient distinctiveness and is merely another decorative design among many.

From a legal perspective, the concern is that granting protection to such a pattern could limit fair competition and unduly restrict the use of common design features.

NAGHEDI, however, maintains that its weave functions as a true source identifier. The brand has cited sales figures and consumer engagement as evidence that the design distinguishes its products from others. Yet without a high level of public recognition, comparable to that of Bottega Veneta, NAGHEDI continues to face the challenge of proving that its pattern has acquired distinctiveness. The case reflects the reality that legal recognition is not automatic, even in the presence of commercial success.

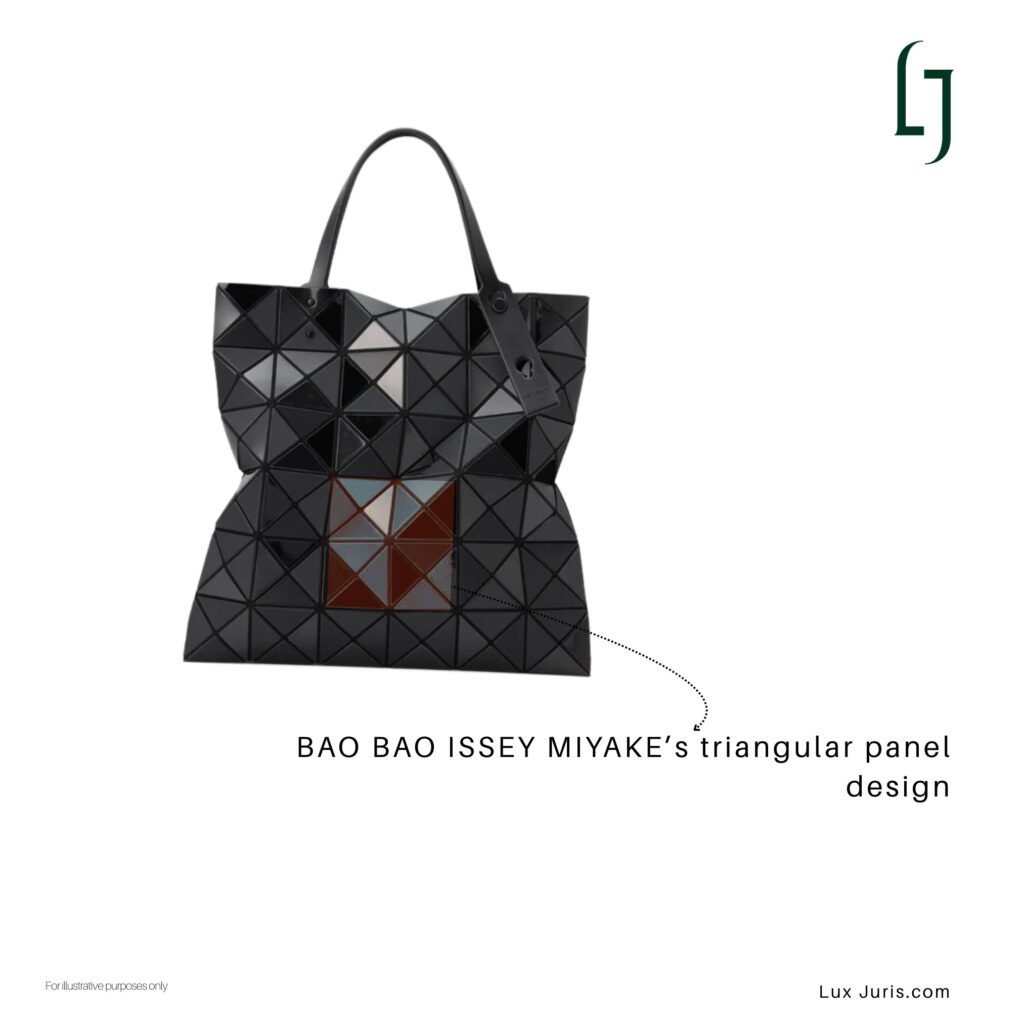

BAO BAO ISSEY MIYAKE: Legal Recognition Through Use

The position was different in the case of BAO BAO ISSEY MIYAKE. The Tokyo District Court ruled in favour of Issey Miyake in a claim against Largu Co., Ltd., which had been selling bags resembling the brand’s distinctive triangular-panel design. Despite Largu’s bags being sold at lower prices, the court held that the similarity could lead to consumer confusion, supporting Issey Miyake’s claim.

This decision illustrates the importance of consistent branding and consumer recognition. Where a pattern has been used widely and is well known to the public, the legal system is more likely to afford it protection against imitation, even where the copy is not identical. The BAO BAO case serves as a useful reference point for brands seeking to rely on unregistered rights or demonstrate acquired distinctiveness.

Challenges for Emerging Brands

Pattern trade marks raise important questions around the limits of legal protection in fashion. Larger brands such as Bottega Veneta are often better placed to meet the evidential requirements needed to obtain registration. They have the resources to run significant advertising campaigns and to prepare detailed submissions in support of their applications. Smaller brands, by contrast, may struggle to meet the same threshold, regardless of the originality of their designs.

There is also a policy consideration, if trade mark protection is granted too readily to attractive patterns without proof of distinctiveness, there is a risk of overreach. Commonplace designs could become monopolised, reducing the creative freedom available to other designers. This is particularly relevant in an industry where visual appeal is central to market success.

Conclusion

The path to securing a pattern trade mark is not based solely on a design’s visual appeal. It requires a clear demonstration that the pattern is distinctive and that consumers associate it with a specific brand. Bottega Veneta’s case shows that with strategic framing and substantial evidence, even an ornamental design can acquire legal recognition. On the other hand, NAGHEDI’s ongoing struggle reflects the challenges faced by emerging brands attempting to establish trade mark rights in a competitive and sceptical legal environment.

As pattern designs continue to play a important role in brand identity, protecting them remains a key concern for fashion brands. Market recognition alone is not enough, a pattern must also withstand legal scrutiny. Without both, distinctiveness risks being only a matter of perception rather than enforceable protection.

Sources:

- WIPO. (2024). Patterns of Protection: Trademarking Designs. Retrieved from https://www.wipo.int/wipo_magazine_digital/en/2024/article_0012.html

- The Fashion Law. (2024). NAGHEDI Looks to Beat Pushback in Bid to Register Woven Pattern Trademark. Retrieved from https://www.thefashionlaw.com/naghedi-looks-to-beat-pushback-in-bid-to-register-woven-pattern-trademark/

- The IP Law Blog. (2013). Weaving a Trademark. Retrieved from https://www.theiplawblog.com/2013/10/articles/copyright-law/weaving-a-trademark/

- Mondaq. (2014). No Logo Required: Bottega Veneta Secures Weave Trademark. Retrieved from https://www.mondaq.com/unitedstates/trademark/286670/no-logo-required-bottega-veneta-secures-weave-trademark

- Marks, H. (2019). BAO BAO ISSEY MIYAKE. Retrieved from https://blog.marks-iplaw.jp/2019/07/21/bao-bao-issey-miyake