Airwair International vs Retail Distribution Concepts (30 September 2025)

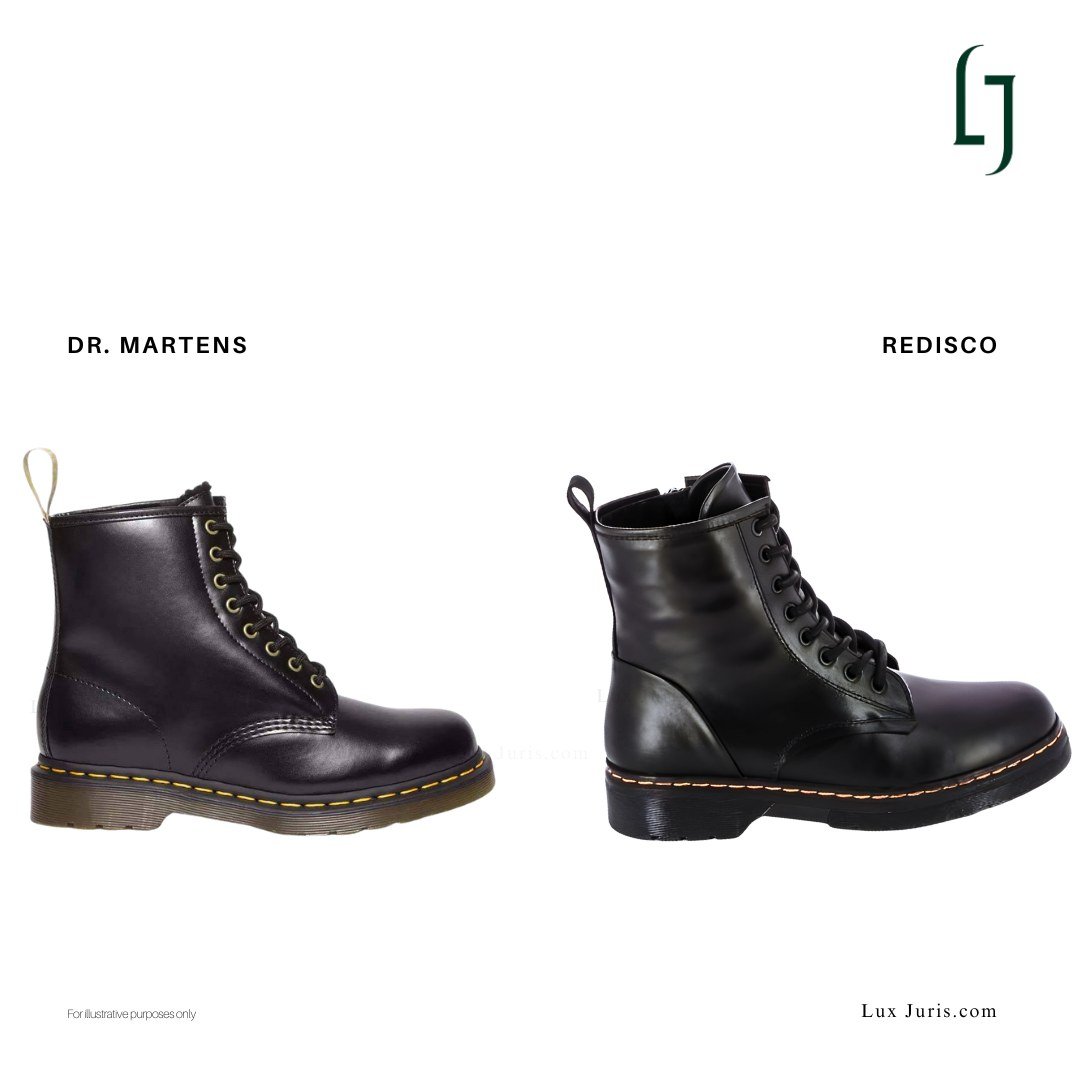

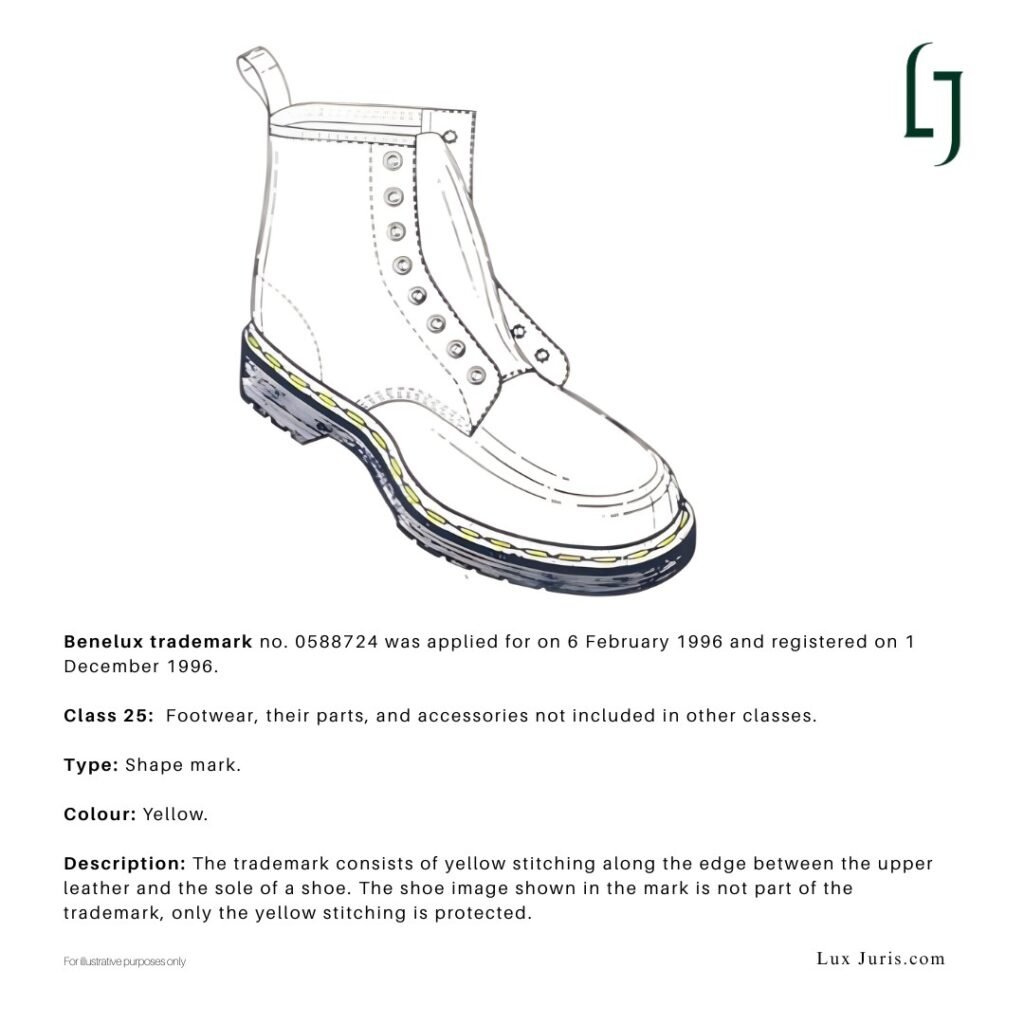

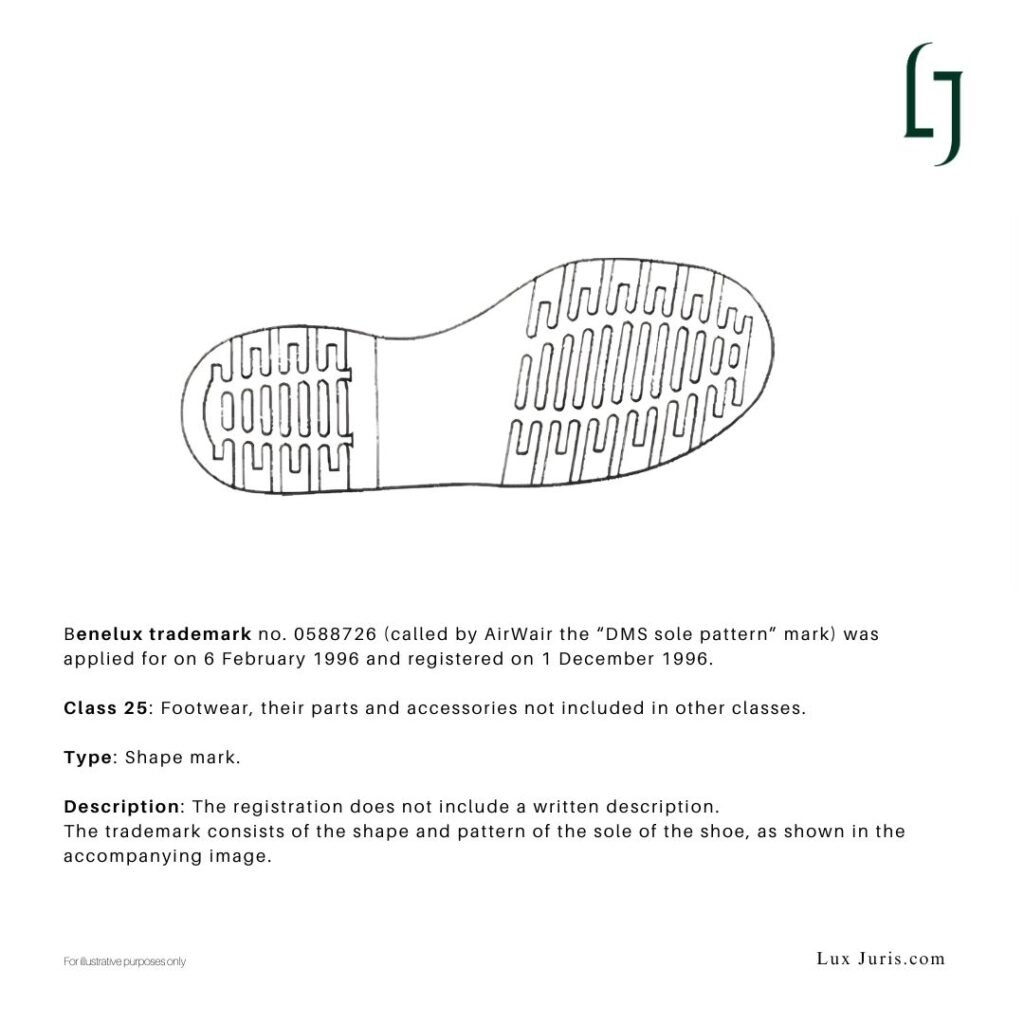

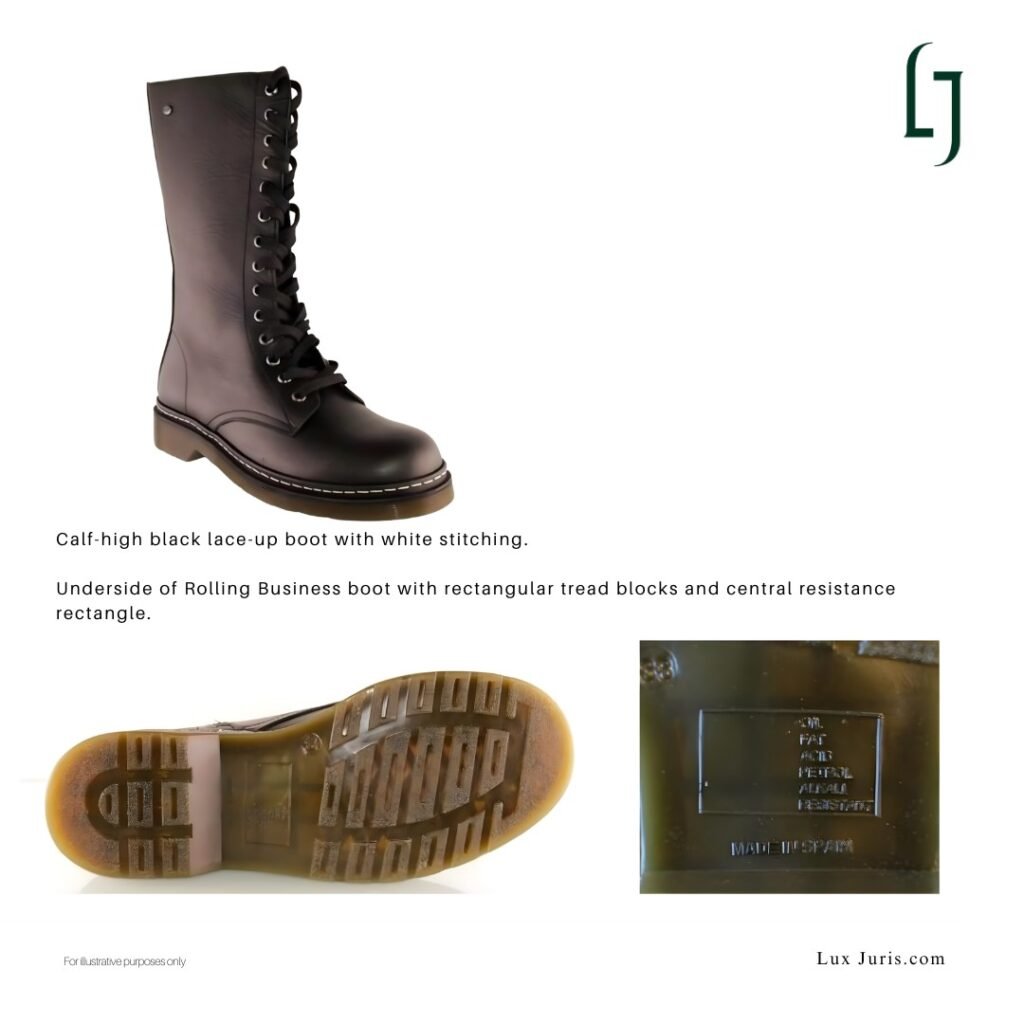

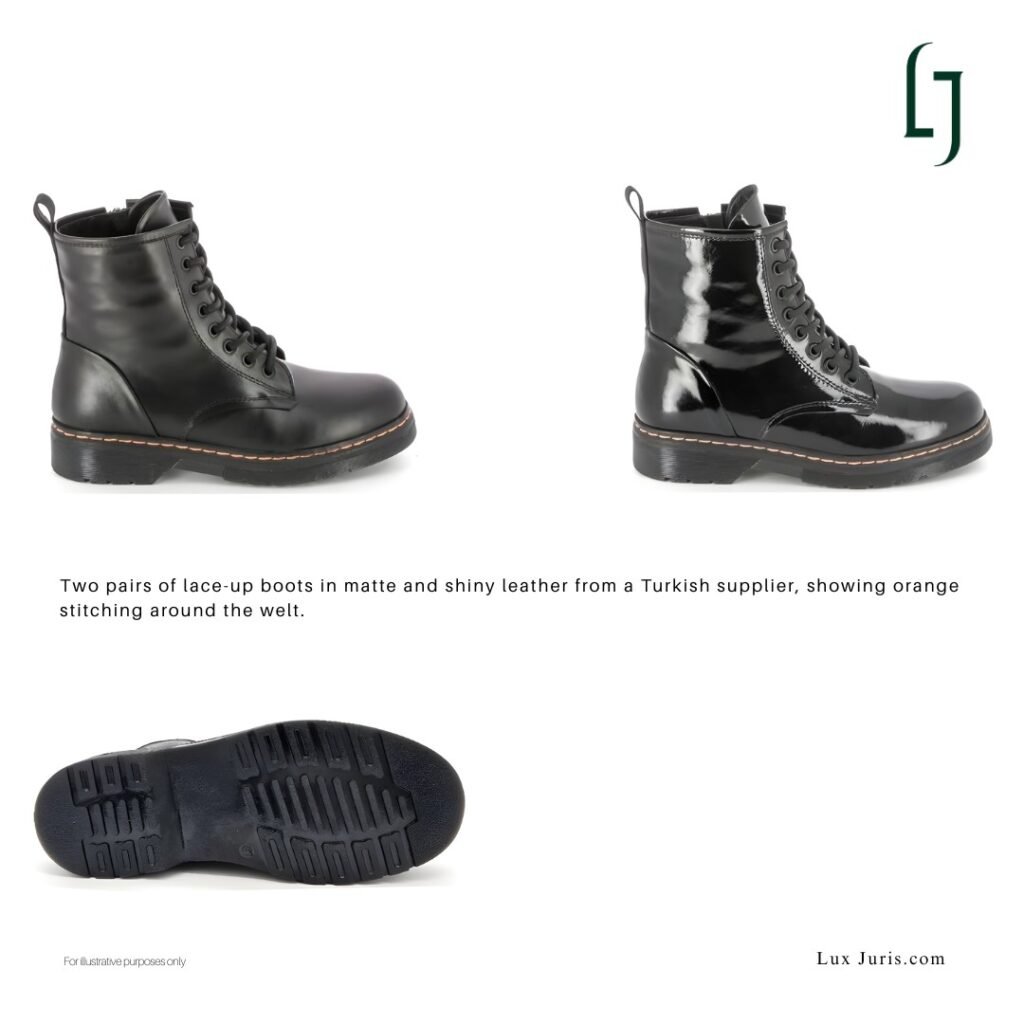

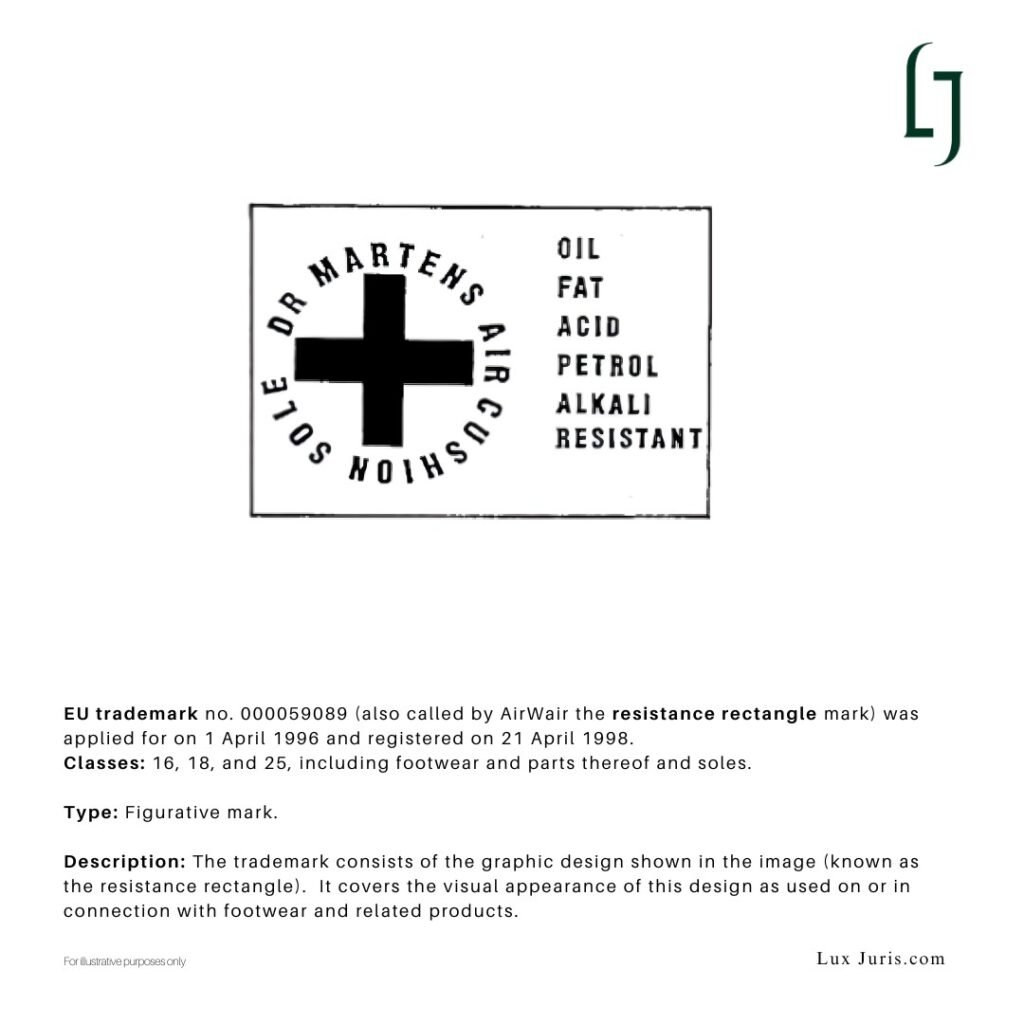

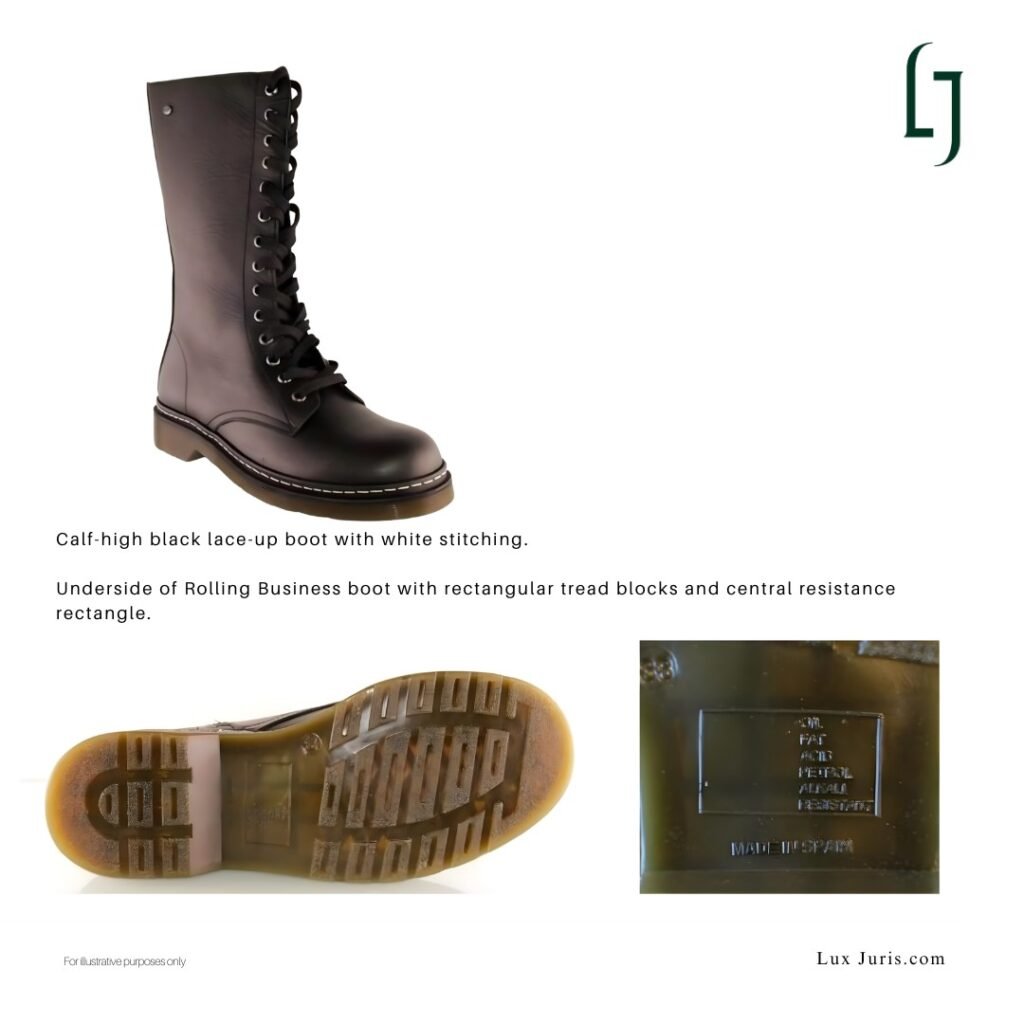

The maker of Dr Martens, Airwair International, brought a case in Belgium against Retail Distribution Concepts BV (Redisco), the company operating the Mano and Pronti shoe stores, over a series of boots that closely resembled its design. The dispute centred on the yellow stitching running around the welt, the translucent sole with its raised grid, and the small rectangular imprint beneath the sole reading Oil Fat Acid Petrol Alkali Resistant.

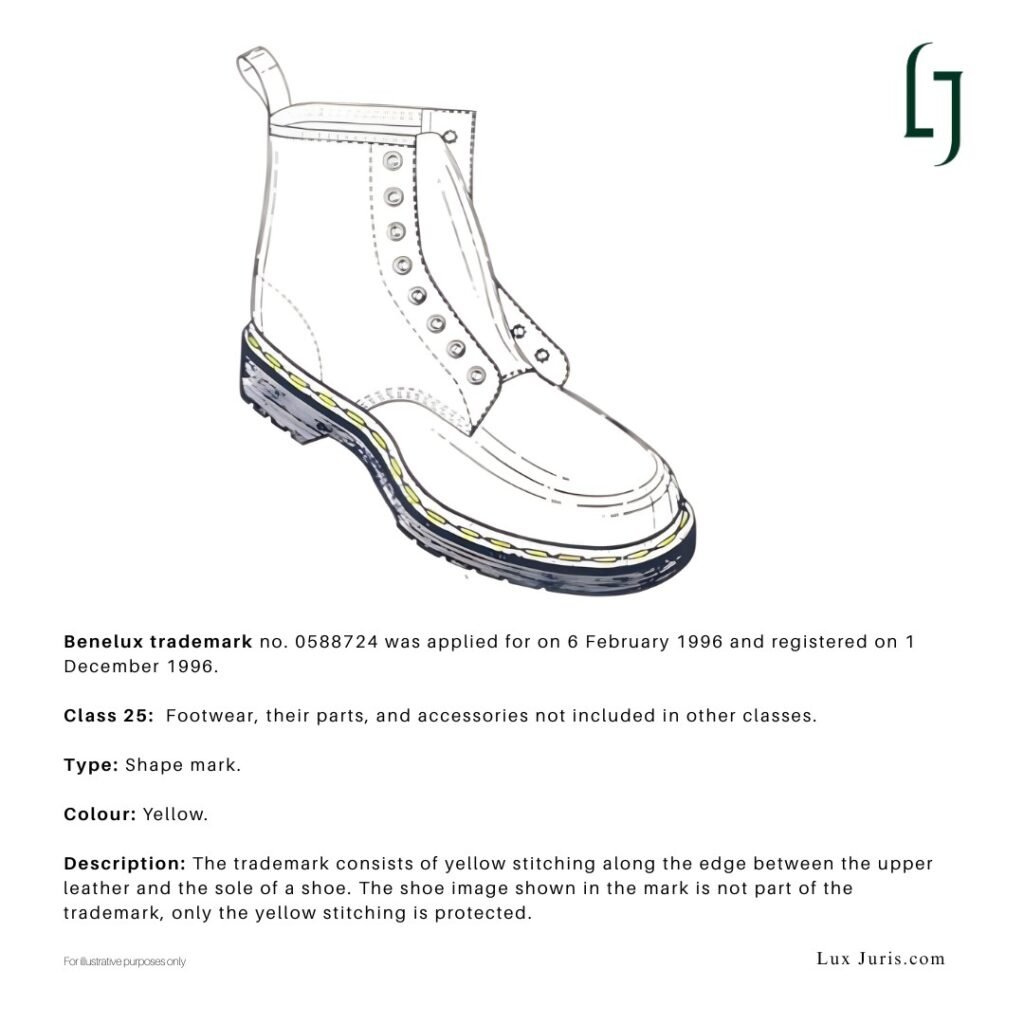

For Dr Martens, these elements were not mere details of construction but the visual codes that had defined its identity for decades. Each was protected through long standing trademark registrations in the Benelux and across the European Union. Redisco argued that such features were common to many boots and could not belong exclusively to one brand.

From sourcing to dispute

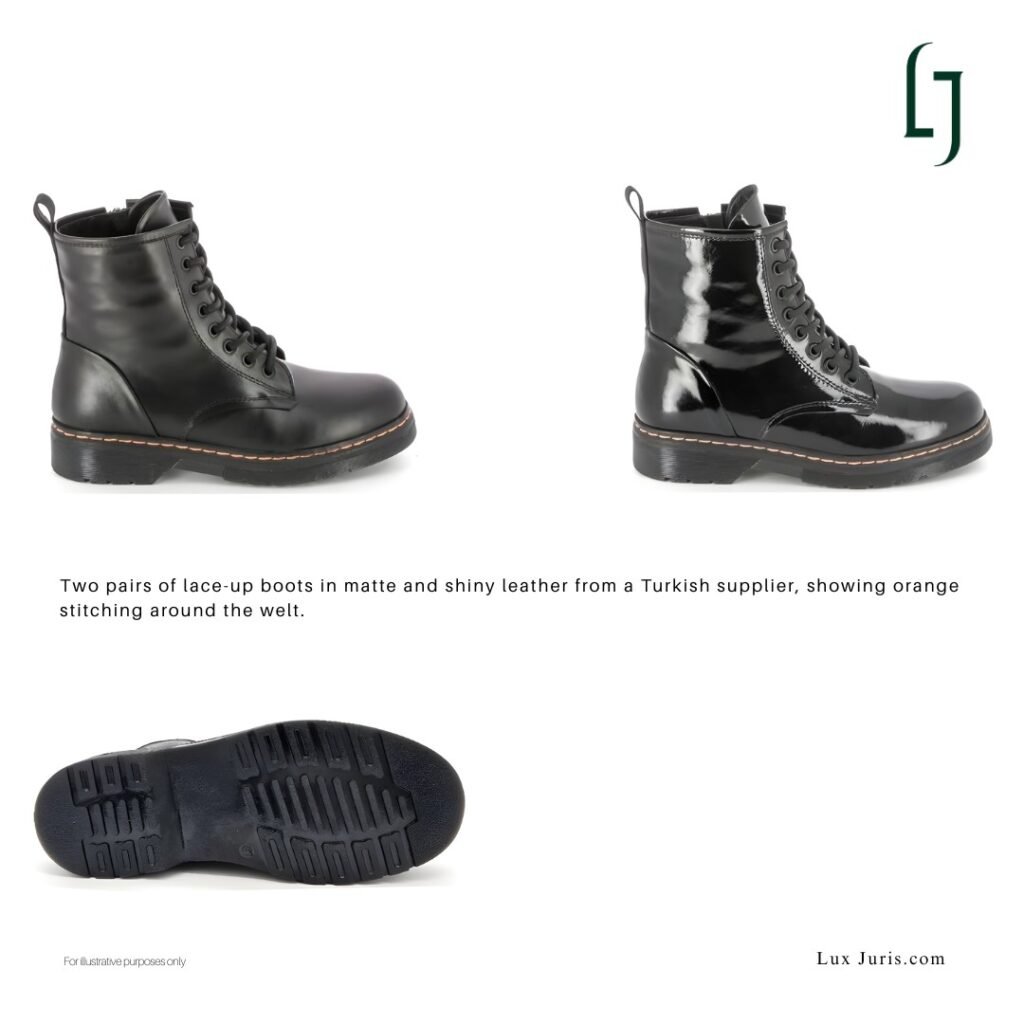

The boots at the heart of the case were sourced from factories in Bangladesh, Spain and Turkey and distributed through Redisco’s Belgian retail network. Dr Martens sent a warning letter in late 2020, asking the company to withdraw the products. Redisco replied that it had already stopped sales and returned unsold pairs, but similar models continued to appear in stores during the following years. This led to formal legal action.

At First Instance

In 2022, the Commercial Court of Brussels dismissed Dr Martens’ claim. It ruled that the sole design lacked individuality, that the stitching and sole imprint were decorative or functional, and that consumers were unlikely to be misled. The court even declared the sole design invalid for want of distinctiveness. Dr Martens appealed, arguing that the court had overlooked how these features, through constant use, had become inseparable from the brand’s visual identity.

The appeal before the Brussels Court

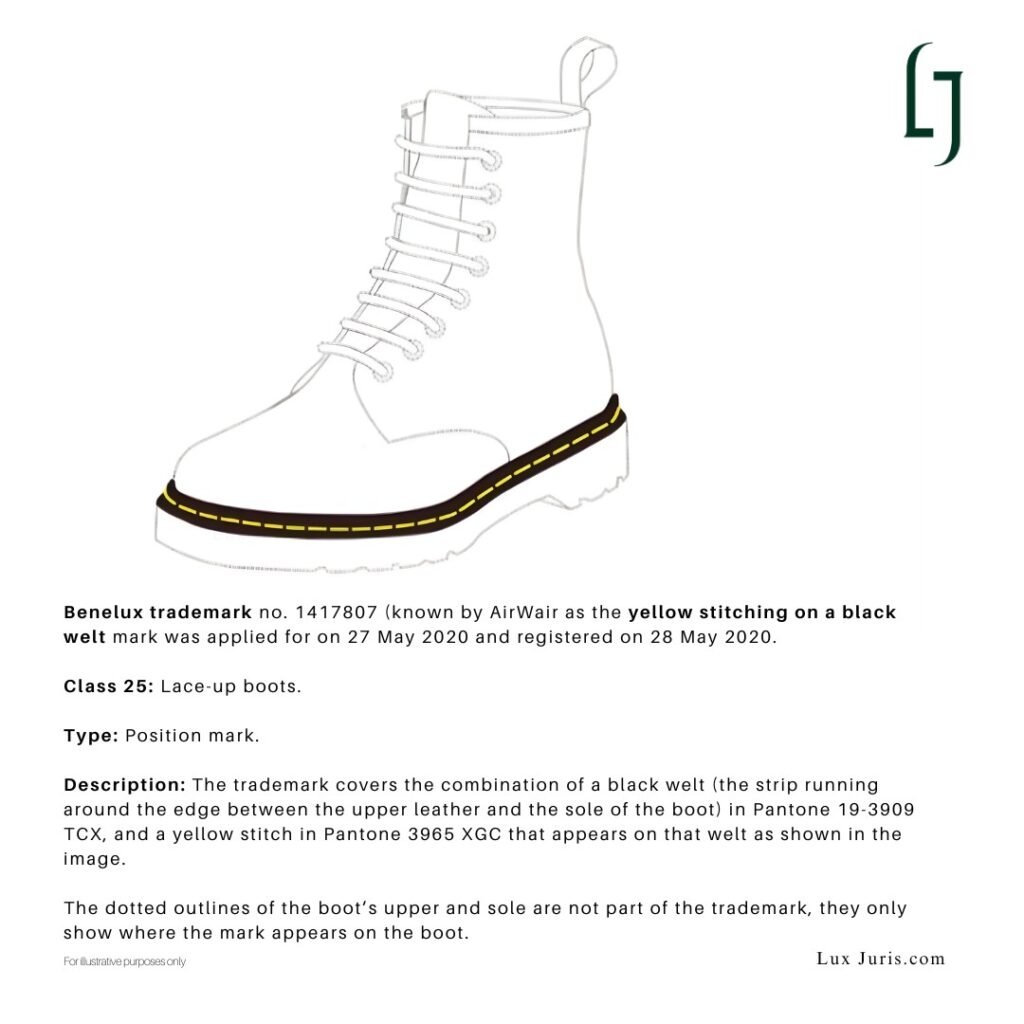

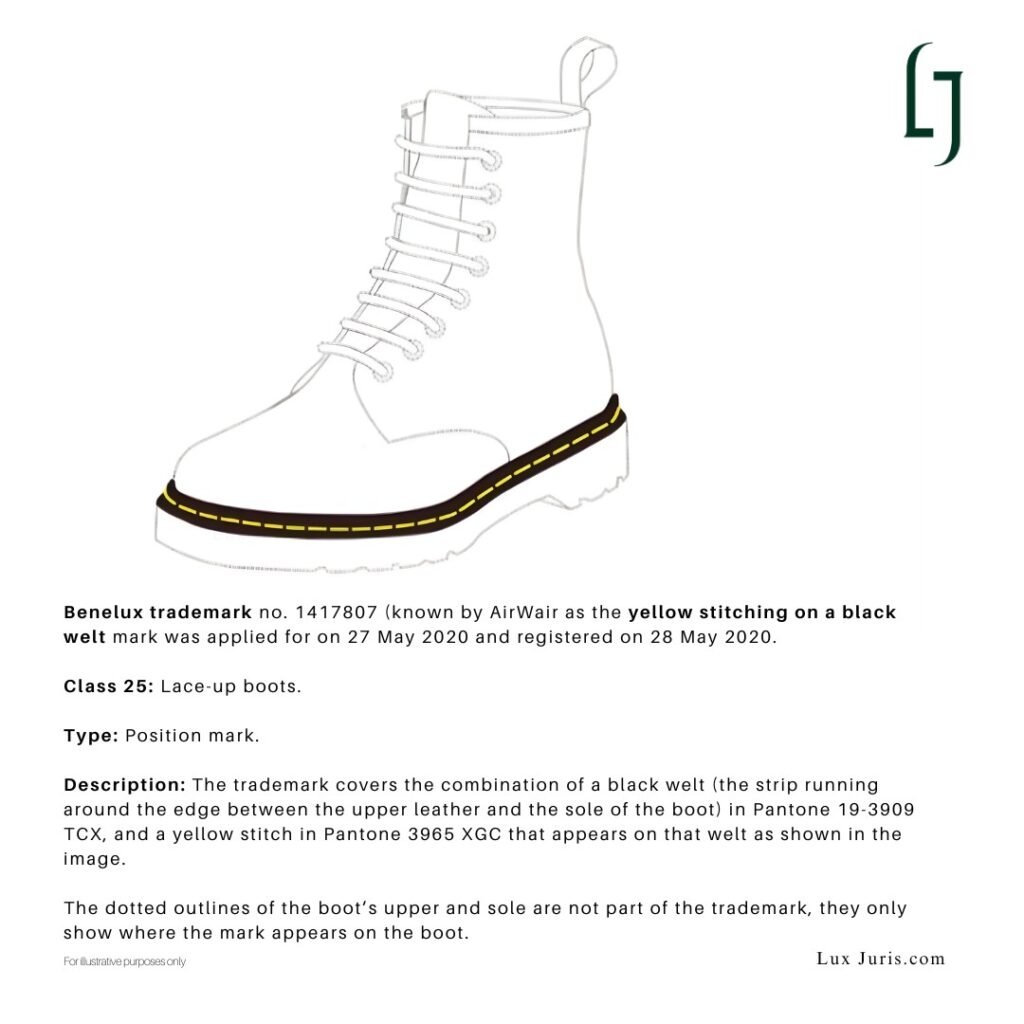

The Brussels Court of Appeal examined the case more broadly. Because a newer registration for yellow stitching on a black welt was already being reviewed before the Benelux Court of Justice, the Brussels judges chose to suspend that issue and concentrate on the older and better established marks: the yellow stitching, the sole design and the resistance rectangle.

The appeal raised two main questions: whether these design details had become distinctive through use, and whether Redisco’s products could confuse the public. The Court relied on photographs comparing genuine Dr Martens boots with the contested pairs.

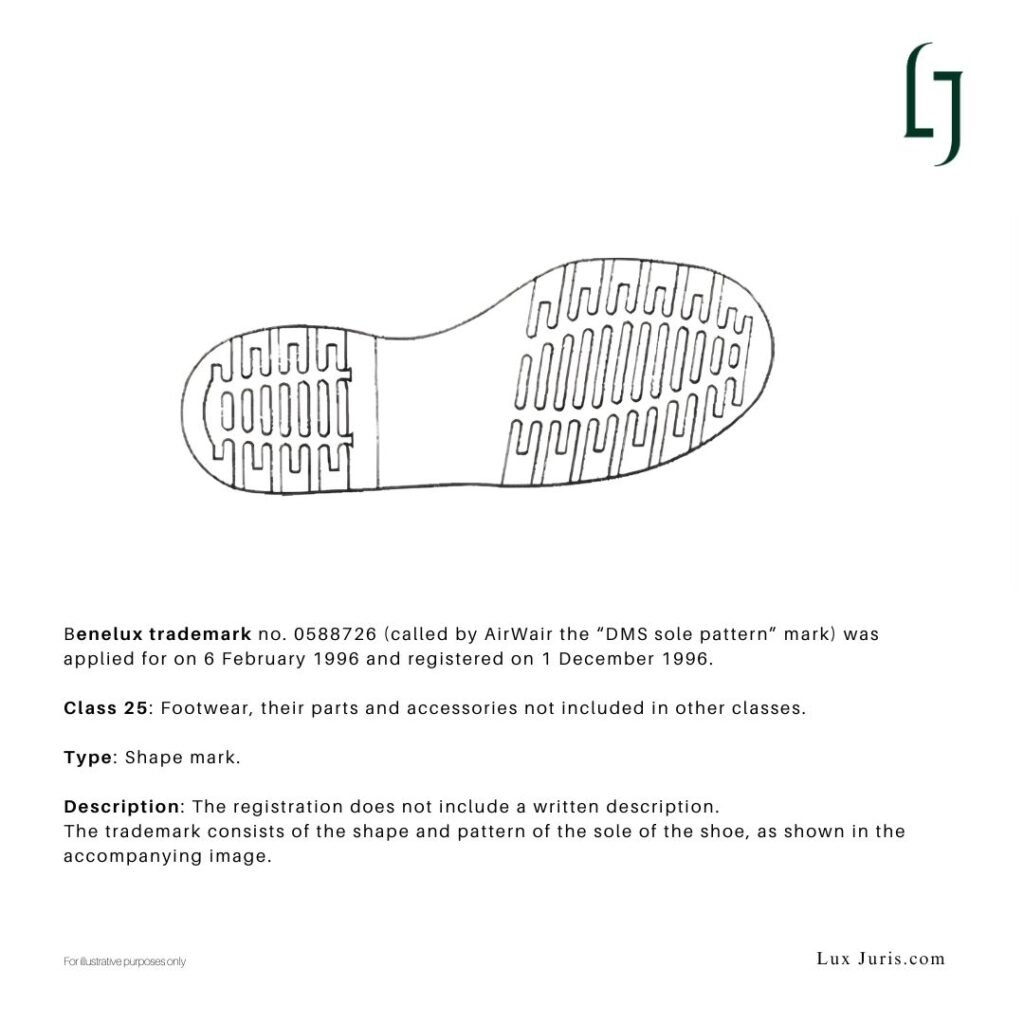

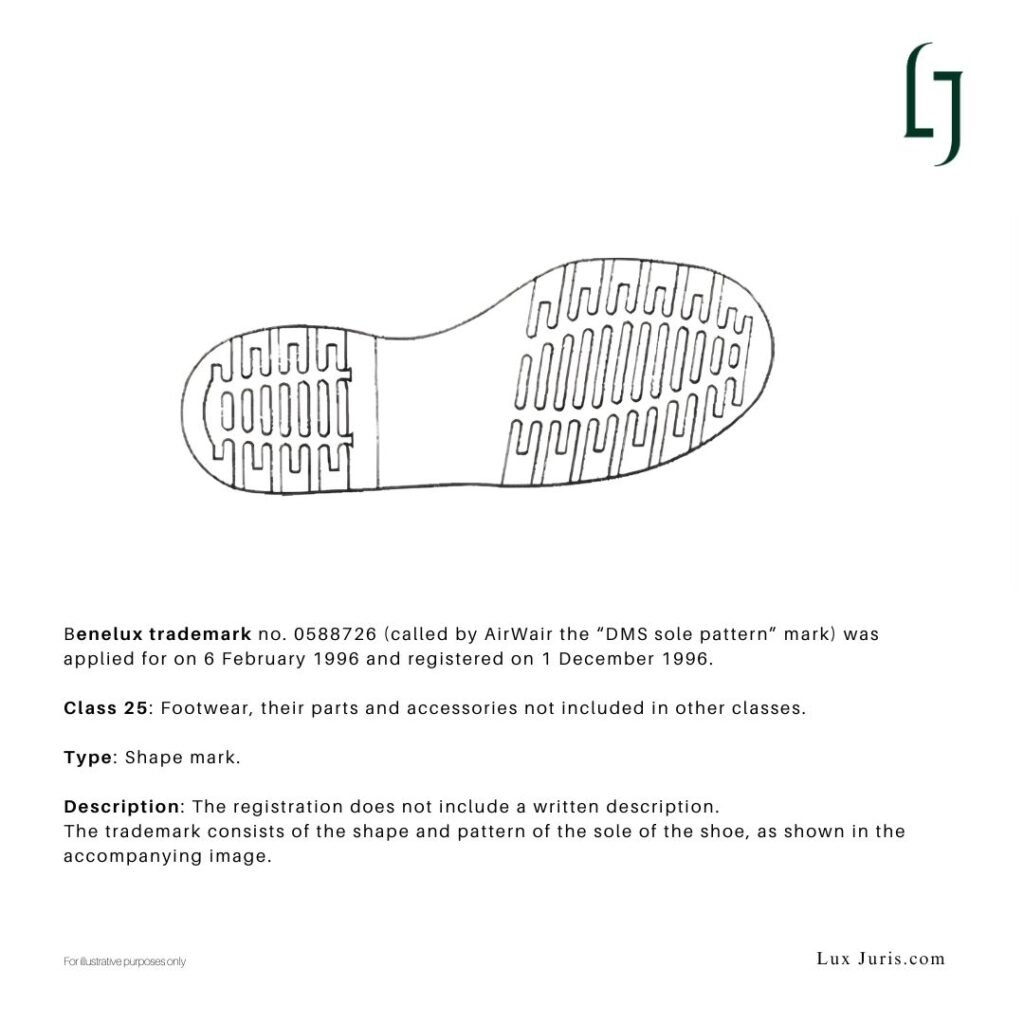

The sole design

The appeal judges disagreed with the earlier finding of invalidity. They described the Dr Martens sole, with its translucent finish and raised rectangular tread, as clearly different from the soles commonly used in footwear. Over years of use and publicity, the public had come to recognise this sole as one of the brand’s most characteristic features.

It no longer served only a technical purpose. Through consistent repetition, it had acquired meaning as a sign of origin. The Court therefore recognised the sole design as distinctive and entitled to protection.

The yellow stitching

The judges accepted that the stitching originates from the Goodyear-welt method used to attach the sole, but they found that the use of bright yellow thread in that position had acquired a distinctive identity of its own. What began as a manufacturing necessity had become a deliberate visual marker.

Dr Martens presented decades of advertising, press coverage and shop displays showing the yellow stitching as a constant feature of its boots. Consumers had come to identify that detail with one maker. Its use was not dictated by function, and its colour choice carried strong association through consistency and visibility.

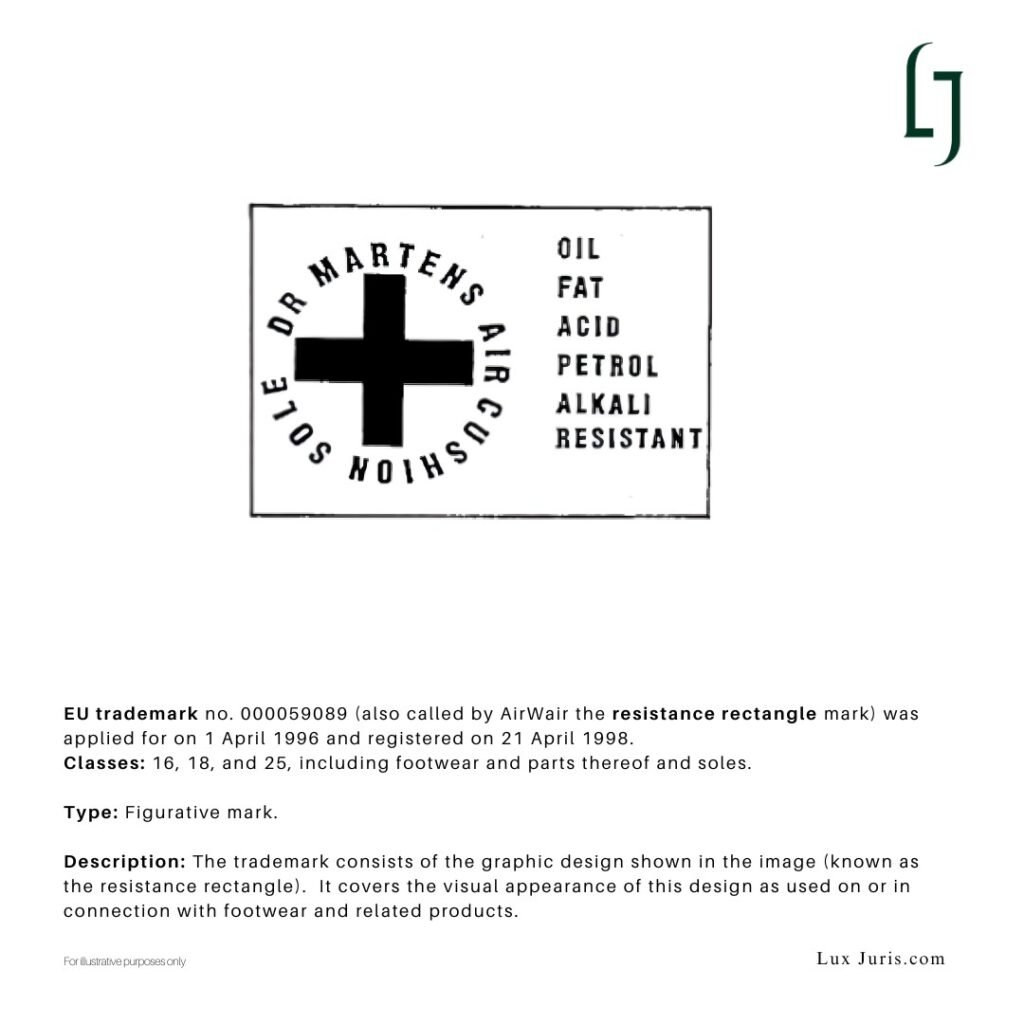

The resistance rectangle

The small rectangular imprint under the sole was treated in the same way. The words themselves were descriptive, but their specific layout, typography and position beneath the translucent sole had, through long repetition, become part of Dr Martens’ visual language.

The contested boots reproduced the same rectangle in the same place, creating an immediate link with the original. The court found the sign distinctive and its imitation an infringement extending throughout the European Union.

Assessment of similarity

The Court compared the images of the contested boots to the originals and concluded that they reproduced the essential visual impression of Dr Martens footwear. The stitching, the translucent sole and the rectangle beneath the foot appeared in the same positions and proportions. Minor variations in shade or surface were not enough to prevent confusion.

Taken together, these elements formed a complete and recognisable structure that most consumers associate with a single source. By repeating that combination, the retailer’s boots risked leading buyers to believe they were genuine or linked to the brand.

Outcome of the appeal

The Brussels Court of Appeal overturned much of the first decision. It reinstated the protection of the sole design and confirmed that the yellow stitching and the resistance rectangle remained valid and infringed. Redisco was ordered to stop selling the disputed boots in the Benelux and to cease using the rectangular imprint across the European Union. Financial penalties were set for any future breaches.

Dr Martens had also requested detailed sales and supplier information, but the Court refused, holding that the injunction itself provided sufficient redress.

How the Court read the visuals

The decision placed unusual weight on visual evidence. The authentic boots showed the yellow stitching contrasting against black leather, the deep translucent sole with its grid pattern, and the engraved rectangle beneath the arch. The contested pairs followed the same composition and alignment.

The Court observed that distinctiveness in design often arises from repetition. The public learns to read familiar features as signals of origin. The strength of those associations can be enough to give legal significance to what began as simple design choices.

Conclusion

The Brussels Court of Appeal gave shape to how a brand can own its visual identity through consistency of design. By confirming protection for the yellow stitching, the sole and the resistance rectangle, the court recognised that distinctiveness can come from long, disciplined use rather than invention. These features were not presented as creative flourishes but as structural elements that, over time, have come to define one origin in the mind of the public.

What secures recognition is not the introduction of new forms each season but the capacity to maintain visual coherence across time. Dr Martens’ success lay in treating its product design as part of its identity system, not as surface detail. The result was a set of features that no longer describe a type of boot but a single maker.

This case also shows that when a brand’s design language becomes recognisable to consumers as a sign of source, it gains protection that endures. That principle reaches beyond footwear, showing how visual consistency, once established in the public eye, becomes part of a brand’s identity, not only aesthetic but legal.

Source: