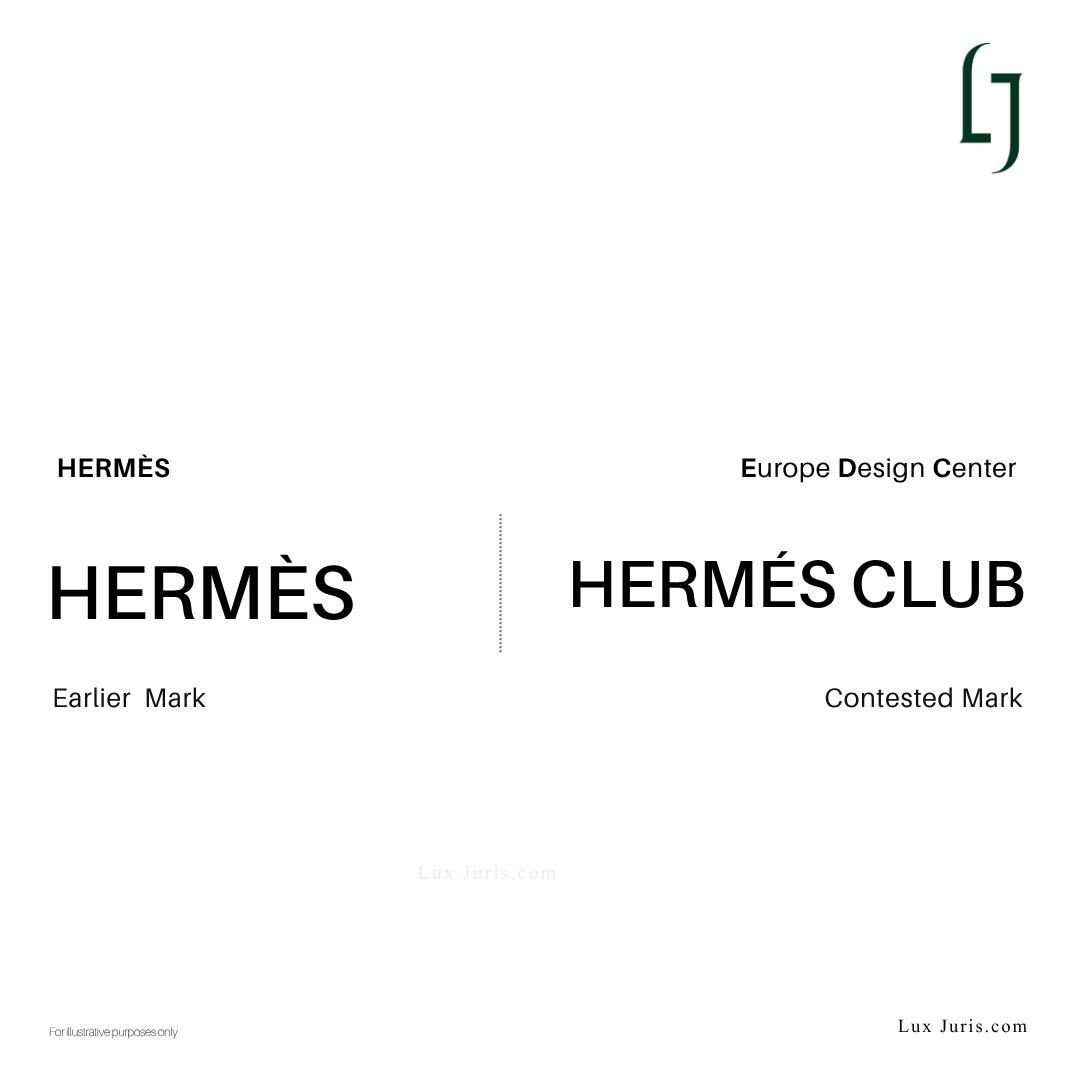

The refusal of the trade mark HERMÉS CLUB offers a useful moment to examine a recurring pattern emerging at the intersection of branding and trade mark law. The filing was submitted by Europe Design Center SAS, a company that has recently pursued the registration of marks structurally anchored to established luxury houses yet lacking independent distinctiveness. The EUIPO rejected the mark in full, concluding that the sign sat too close to the name Hermès to function as an autonomous indicator for the goods and services claimed.

This was not an isolated filing strategy. Only weeks earlier, the same applicant sought protection for FENDI CLUB, prompting another opposition. That trade mark was partially refused, with registration denied for goods and services overlapping with Fendi’s existing rights, including apparel, footwear, leather goods, jewellery, advertising and design services. The mark was allowed to proceed only for “precious metals and their imitations”, a narrow and commercially detached category. Evaluated together, these decisions reveal a pattern rather than a procedural coincidence, and it is that pattern which merits focus.

The Familiarity Problem

At first glance, the structure appears disarmingly simple, attach a recognisable luxury name to a neutral qualifier such as “Club”, and the result looks culturally aligned, marketed and ready for consumption. The intention may be to evoke exclusivity rather than imitate identity, yet legally and commercially those concepts cannot be separated. Trade marks operate in the consumer’s memory, not in theoretical nuance. Memory does not analyse accents or spacing, it identifies similarity and assumes connection.

No Proof of Reputation Was Required

No evidence of acquired distinctiveness, consumer perception or advertising spend was necessary. The dominant element remained HERMÈS, and the added term did nothing to distance the new sign from the source brand. The resulting impression was not a new origin, but a brand extension.

Association Is Sufficient

It is worth repeating that the law does not require direct confusion. A sign need only create a link strong enough to suggest affiliation, licensing or hierarchical brand architecture. Luxury brands routinely use modifiers for diffusion lines, capsules, collaborations and membership tiers. In that context, HERMÉS CLUB reads as an internal Hermès initiative, not an external business. That inference alone is fatal to registrability.

The Cost of Derivative Naming

From a business perspective, building a name around existing brand equity may feel strategic. In practice, it constrains growth. A name that cannot withstand opposition cannot scale, cannot expand territorially, cannot secure investment and cannot mature into enforceable brand equity. A trade mark should open markets, not depend on another’s identity to justify its existence.

Guidance for Emerging Brands

A viable brand name is not one that merely sounds expensive or familiar. It is one that is distinctive, defensible and capable of operating independently across markets and product categories. The moment a proposed name relies on another for meaning, positioning or perceived value, it stops being an asset and becomes a liability.

Words such as club, atelier, maison, studio, edition or house do not create a new trade mark when attached to an existing name. They change the style of the phrase, not the likelihood of confusion or its legal outcome.

Conclusion

Viewed together, the Hermès and Fendi cases point to the same reality, brand names that resemble an existing luxury trade mark do not create a new identity. Instead, they lead to conflict and refusal. Well known brands defend their names actively, and they do not become linked to another business simply because the wording sounds familiar or exclusive.

A strong brand stands on its own. It begins with a name that is clear, original and capable of protection. It does not depend on similarity, and it does not borrow recognition to appear established.

Source: