The European Union Intellectual Property Office has once again clarified how far a designer may go when drawing inspiration from a familiar form. On 7 November 2025, the Invalidity Division ruled in favour of Crocs in proceedings against FLAMEshoes Slovakia, finding that the latter’s foam clog produced the same overall impression as the Crocs design. Though predictable in outcome, the decision provides a clear view of how individual character is assessed and how publication within the EUIPO register amounts to disclosure.

The Dispute and Its Context

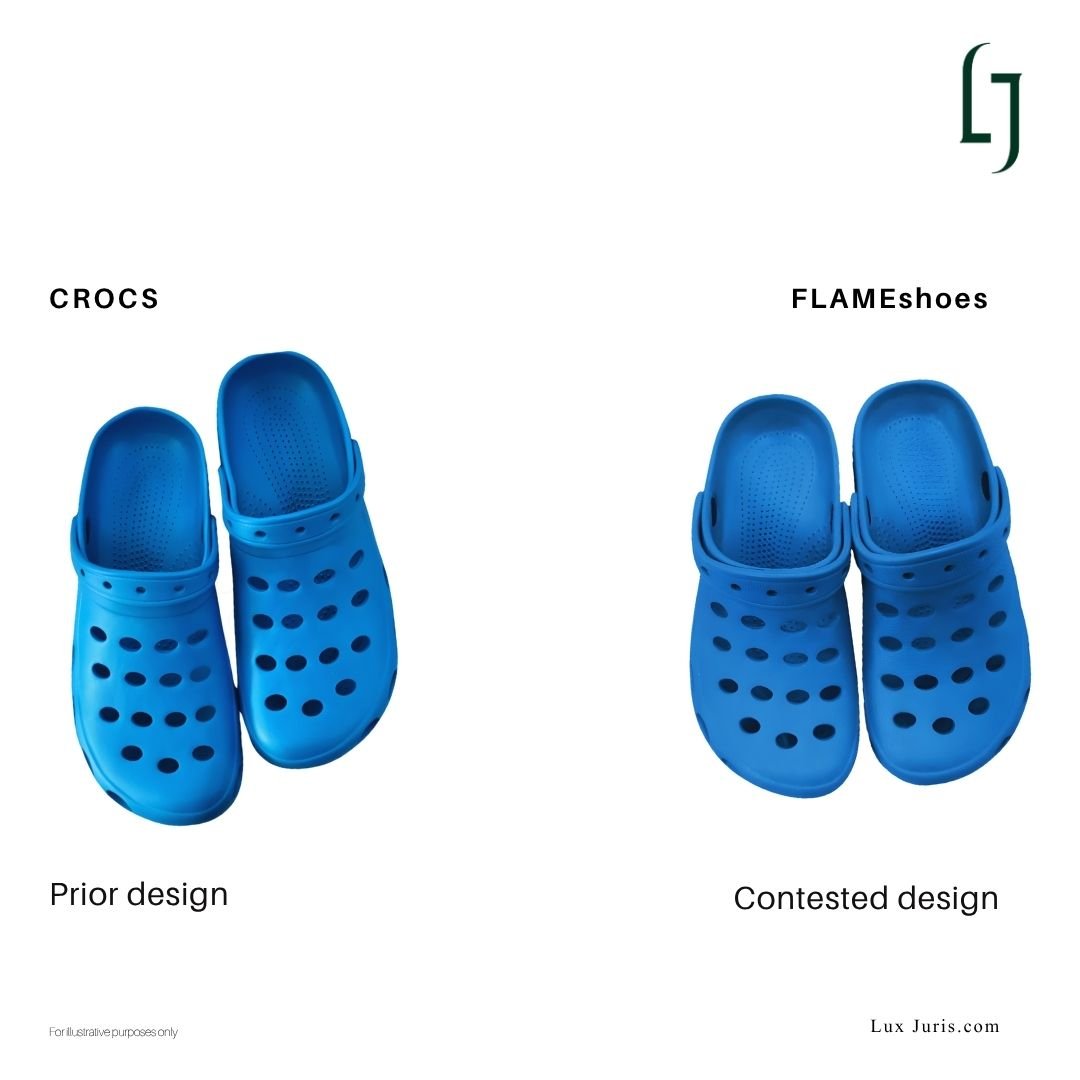

Crocs brought proceedings after the Slovak company sought protection for a clog design that appeared indistinguishable from the well known Crocs silhouette. The challenge was based on the lack of individual character, as the new design failed to create a different overall impression on the informed user.

The case was examined under the updated framework introduced in May 2025, which consolidated earlier design legislation without changing the core standards of validity.

The Applicant’s Claim and the Holder’s Defence

Crocs relied on its earlier published design, maintaining that both clogs shared the same proportions, configuration, and visual detailing.

FLAMEshoes argued that Crocs’ design had never been made available to the public through commercial circulation and that publication in the EUIPO register alone could not make it known.

Crocs responded that publication by the Office itself makes a design publicly visible and therefore available as a point of reference in later assessments.

The Question of Disclosure

The Invalidity Division confirmed that publication in the EUIPO register constitutes disclosure on its own. Once a design appears there, it is considered accessible to those active in the relevant field, even if the product has not been marketed.

This position maintains the transparency of the design system. A published design becomes part of the visible design record that may be taken into account when assessing whether a later filing is genuinely new. The Division therefore accepted the earlier Crocs clog as a valid basis for comparison.

Comparison of designs

With disclosure established, the Office turned to the designs themselves. Both concerned foam clogs and shared the same rounded toe, perforated upper, and pivoting heel strap fixed by a circular rivet. Their shape, massing, and pattern of perforations were almost identical, and even the tone of blue contributed to the same visual impression.

The informed user was identified as someone familiar with clogs, attentive to their form but not technically trained. The designer’s freedom in this field was described as broad, limited only by comfort and ergonomic constraints, a degree of freedom that increases the expectation of visual distinction.

When considered as a whole, the contested design gave the same impression as the earlier one. Any differences were too slight to be noticed in normal use. The design therefore lacked the distinctiveness required for protection.

Findings

For design protection to apply, a product’s appearance must be new and capable of standing apart from what already exists. This decision shows how those two conditions work together. Once a design has been published, any later design that repeats its main features cannot meet that threshold.

The FLAMEshoes clog, in this light, was not a new interpretation but a repetition. Its form, proportion, and detailing reflected a design already visible in the register.

Decision

The Invalidity Division declared the design invalid, ruling in favour of Crocs. Its reasoning followed a straightforward approach: publication counts as disclosure, design freedom carries responsibility, and the deciding factor remains the overall impression perceived by the informed user.

Conclusion

The case focuses on the importance of a design’s shape rather than merely on footwear. The Crocs clog is simple in appearance yet has a distinctive form recognised across markets. The ruling shows that simplicity does not make a design free to copy and actually makes it more important to be creative within those design limits.

By treating EUIPO publication as disclosure, the Office establishes a clear point of visibility. Once recorded in the register, a design becomes part of the visible design record of the Union, not free for use, but available as a reference for what already exists. Designers may study it, respond to it, and move beyond it, but not reproduce it.

In the end, Crocs vs FLAMEshoes shows that originality in design law lies not in decoration but in proportion and structure, and that even the most utilitarian form can carry a distinct identity.

Source: