Luxury counterfeits in China continue to present serious challenges for global brands, even as trademark enforcement becomes more structured. Although legal protections have strengthened, consumer demand for imitation goods remains high, shaped by cultural familiarity, affordability, and the pursuit of social status. Addressing this issue requires more than litigation. It calls for a closer examination of how intellectual property rights intersect with everyday purchasing behaviour.

This article presents trademark cases involving Burberry, Manolo Blahnik, and Moncler, together with informed perspectives on consumer behaviour and counterfeit demand in China.

Legal Action Against Luxury Imitation and Counterfeiting in China: Three Brand Responses

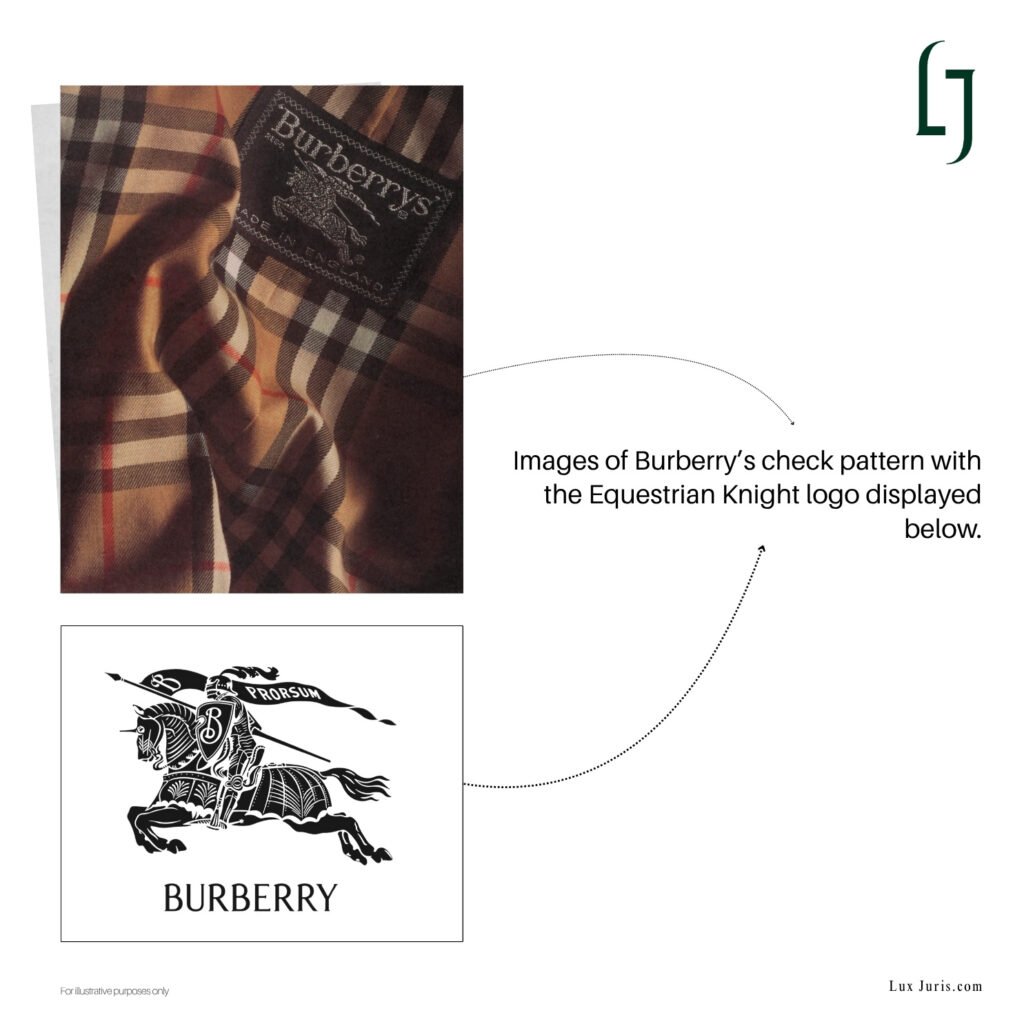

Burberry: Well-Known Status and Protection Against Lookalikes

In 2023, Burberry obtained a favourable decision from the Jiangsu Provincial High People’s Court in a case involving Xinboli Trading Shanghai. The defendant had sold goods under the “BANEBERRY” mark, replicating Burberry’s check pattern and the Equestrian Knight logo. The court awarded RMB 6 million in damages and confirmed the well-known status of Burberry’s trademarks in China. This status enabled the application of stricter standards in evaluating infringement, particularly in cases involving deliberate imitation.

Manolo Blahnik: The Long Road to Reclaiming a Trademark

Manolo Blahnik’s trademark struggle in China lasted over two decades. In 1999, a Chinese individual filed for the “Manolo & Blahnik” mark, effectively blocking the brand from using its own name in the country. Although the brand was well established internationally, it was unable to operate under its own identity in China until 2022, when the Supreme People’s Court declared the earlier filing to be in bad faith. The ruling was made possible by amendments introduced in 2019, which allow for greater scrutiny of bad faith trademark applications. The outcome illustrates the vulnerability of foreign brands that delay registration, even when their reputation is already well established abroad.

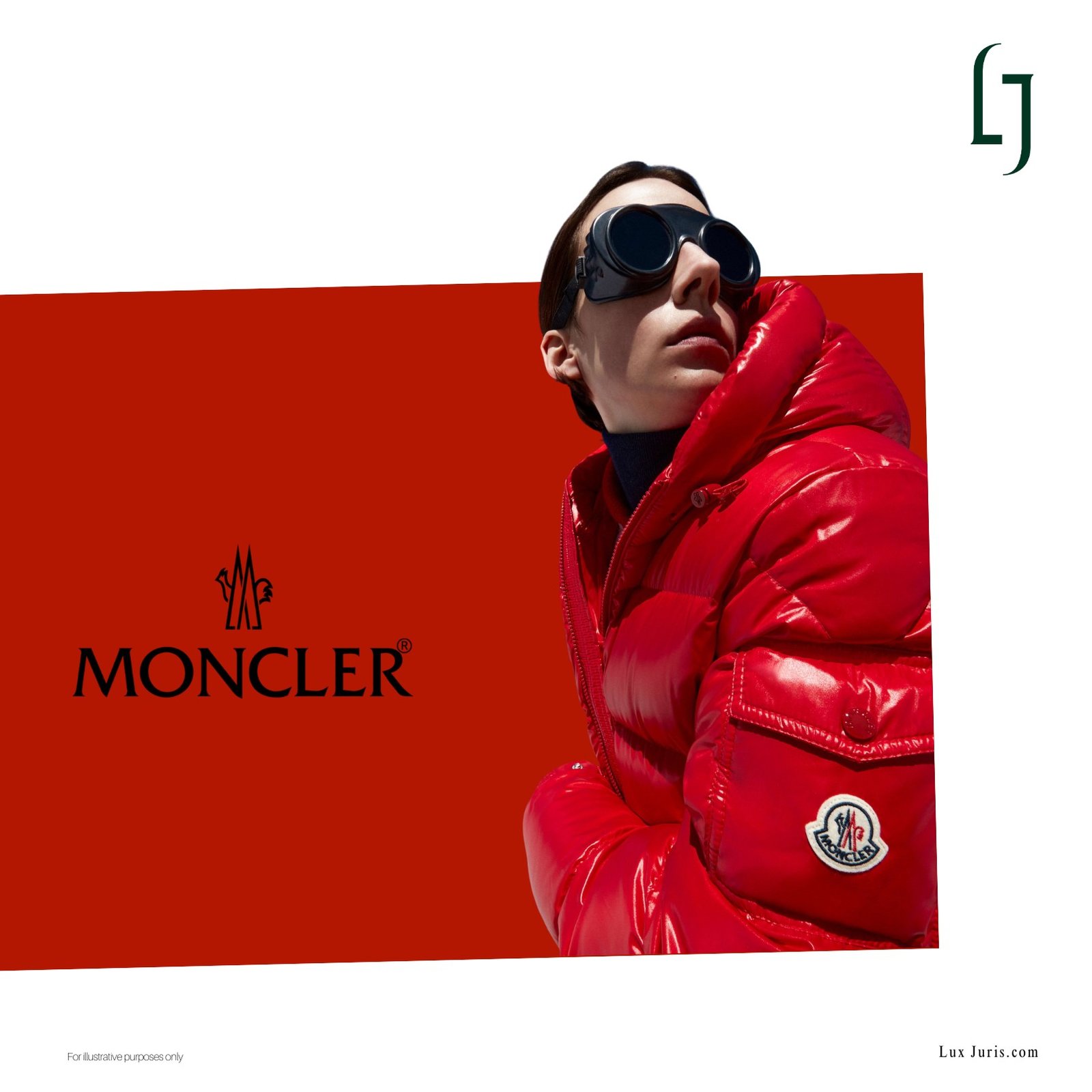

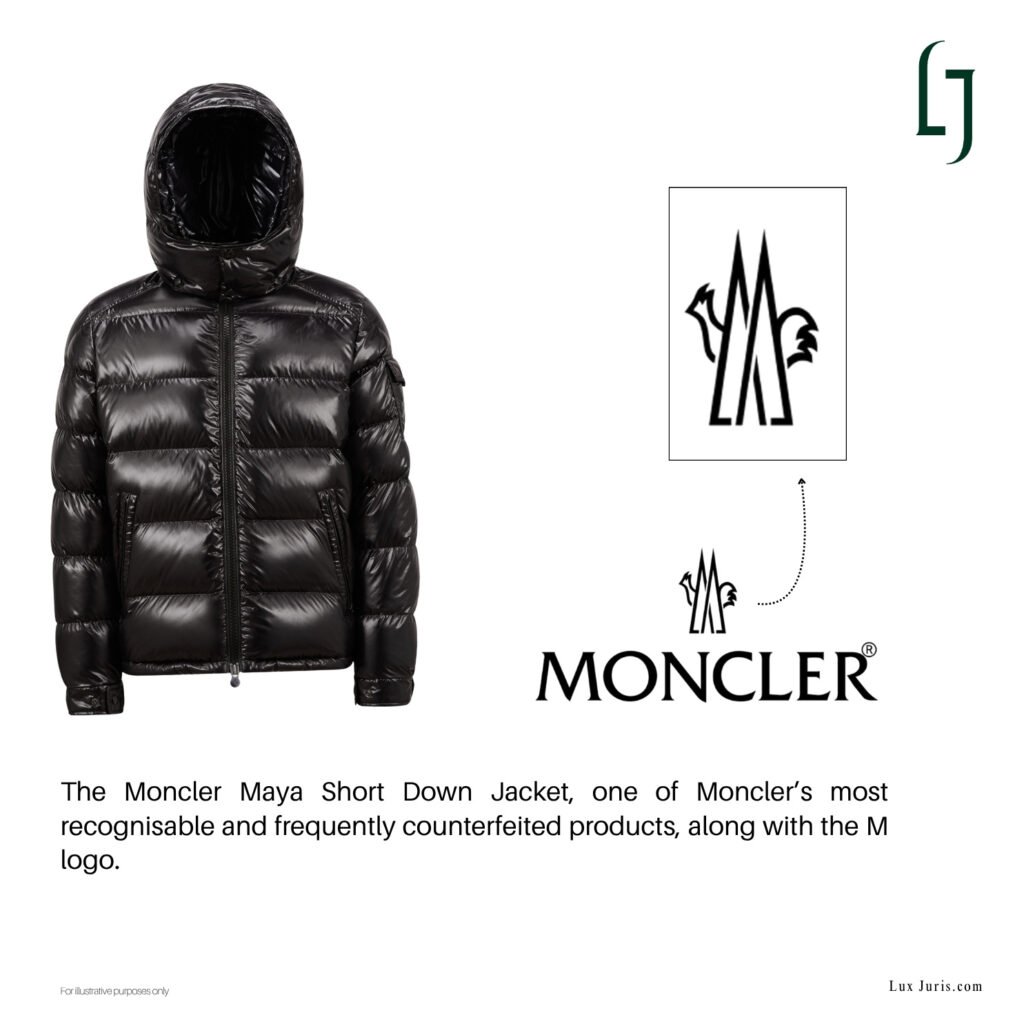

Moncler: Multi-Level Enforcement in Courts and Online Platforms

Moncler has responded aggressively to counterfeiting in China. In one example, the brand brought civil proceedings against companies using the Mengking mark to sell goods mimicking Moncler’s “M” logo and colour scheme. The Hangzhou Intermediate People’s Court awarded RMB 4.7 million in damages, and the ruling was later upheld by the Zhejiang High Court.

Moncler has also collaborated with online platforms to remove infringing listings and websites, recognising that enforcement must take place across physical and digital spaces. However, enforcement efforts alone do not explain the persistence of counterfeit activity.

To fully understand the scale of the issue, it is necessary to examine the other side of the market.

Understanding Imitation Through Consumer Behaviour

Enforcement efforts in China continue to face resistance from persistent consumer demand. Brand awareness alone does not deter infringement. In fact, the more recognisable a brand becomes, the more likely it is to be targeted. Familiarity with a brand can increase its desirability, especially when genuine products are priced out of reach. In such cases, consumers may turn to lower-cost alternatives that offer a similar visual appeal without the financial barrier.

The emphasis is frequently on visual similarity rather than product origin. Imitation goods are not always intended to deceive. For many consumers, they offer a way to participate in status-driven consumption at a reduced price point.

Cultural and commercial norms further shape how imitation is perceived. The concept of Shanzhai, often associated with unauthorised reproduction of branded goods, has contributed to a more permissive environment. In such cases, imitation is not automatically viewed as infringement. Lookalikes may be seen as functional equivalents, particularly in markets where access to genuine products remains limited.

Although some consumers are guided by reputational concerns or an appreciation for brand heritage, these considerations do not consistently outweigh the appeal of affordability and appearance. In a market shaped by both economic constraints and cultural acceptance, enforcement alone cannot fully address the demand for imitation.

Conclusion

China’s enforcement infrastructure is gradually improving, particularly in cases involving well-known marks or clear instances of bad faith. However, legal measures alone cannot resolve the demand for counterfeits, which is shaped by economic pressures, social signalling and cultural acceptance.

The cases involving Burberry, Manolo Blahnik, and Moncler show that trademark rights can be enforced under the right conditions. Yet in a market where imitation is normalised and visibility enhances desirability, enforcement has limited influence on consumer behaviour. Unless the underlying drivers of demand are addressed, even well-protected trademarks remain vulnerable.

For brands, success in China takes more than just registering a trademark. It also requires regular checks for infringement and meaningful engagement with the values that influence consumer choice. Protecting brand value means understanding not only what is copied, but why.

Sources:

Counterfeit Luxury and Trademark Protection in China, ResearchGate